Title Your Graphic

Most of the time, putting the data into graph form isn’t quite enough. In fact, it’s just the start. You created this graph to help you tell the story of your data and to ensure your message gets across, you need to be clever about the titles you include.

You’ll find most communicators title their graphs according to the content they display. It might say “Year-over-year Performance” or “Weekly Average Ticket Sales.” But if your message is about how weekly average ticket sales are down 10 percent compared to last year, you might consider calling your graph “Average Ticket Sales are Decreasing.”

The video below is a demonstration of how to make a graph tell your story by making it easier to read and making the title active:

You can view the transcript for “Persuasive Presentation: How to Make Graphs More Powerful” here (opens in new window).

Captions for Your Graphic

Captions usually indicate the source of information. If your sources and communications are not produced by people within your company, then this is an important step. Captioning the source gives your information credibility and strengthens your story. It also gives credit to the producers of the work.

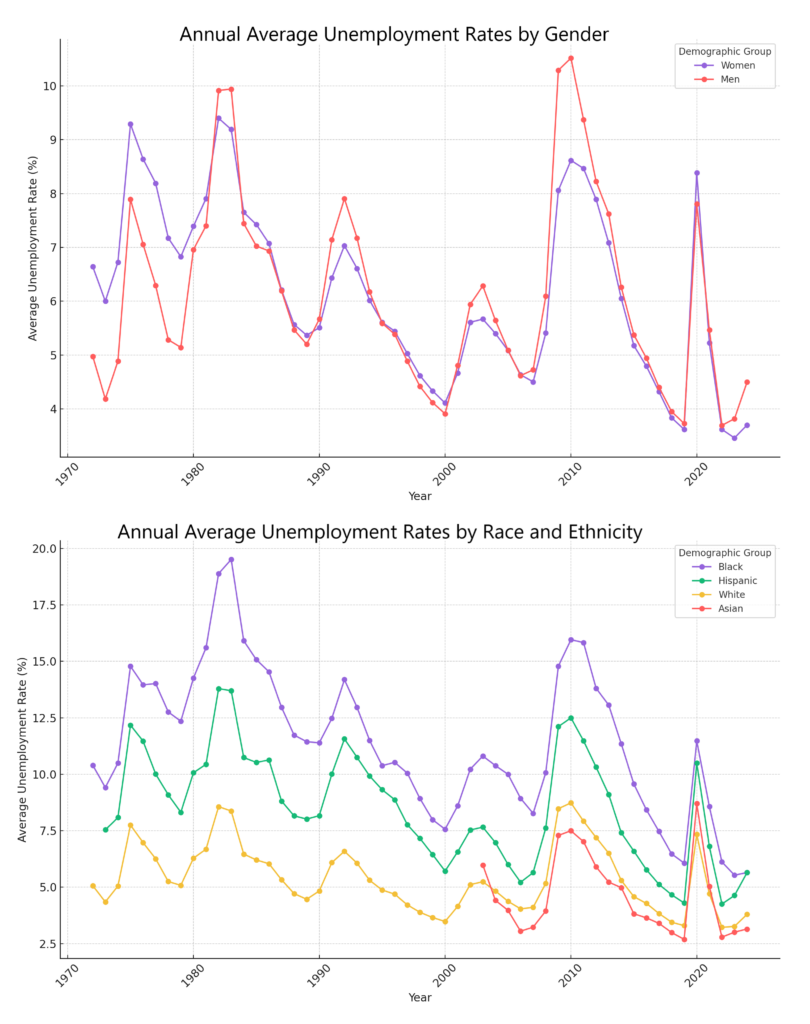

You can also use captions to convey other pertinent information such as the variables being plotted, the units of measurement, or any relevant context. You may want to include the sample size of a survey the graph is illustrating or additional background information about the data (as shown in Figure 1). Using captions in this manner helps the reader draw the conclusion that you intend.

A caption on a graph can be ineffective when there is more information captioned than is of interest to your audience, or if information included in the caption would be better displayed elsewhere.

Visual media should always make a point clearer, so make sure your graph’s format, titles, and captions are working for you rather than against you.