The Hindu—Arabic Number System

Our own number system, composed of the ten symbols {[latex]0[/latex],[latex]1[/latex],[latex]2[/latex],[latex]3[/latex],[latex]4[/latex],[latex]5[/latex],[latex]6[/latex],[latex]7[/latex],[latex]8[/latex],[latex]9[/latex]} is called the Hindu-Arabic system. This is a base-ten (decimal) system since place values increase by powers of ten. Furthermore, this system is positional, which means that the position of a symbol has bearing on the value of that symbol within the number. For example, the position of the symbol [latex]3[/latex] in the number [latex]435,681[/latex] gives it a value much greater than the value of the symbol [latex]8[/latex] in that same number. We’ll explore base systems more thoroughly later. The development of these ten symbols and their use in a positional system comes to us primarily from India.[1]

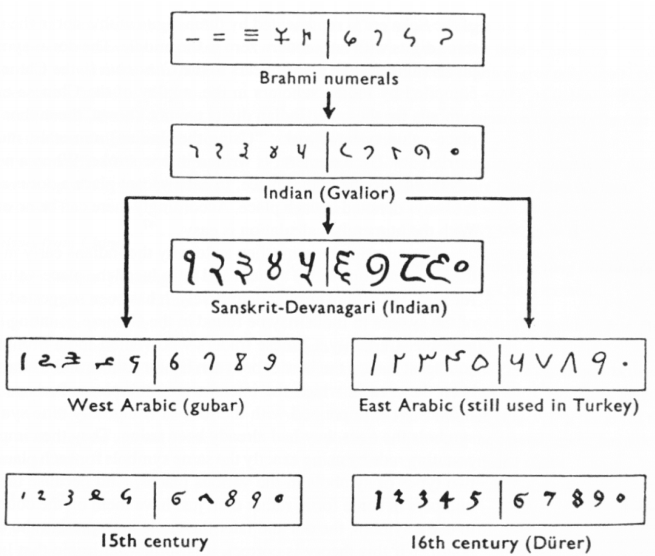

It was not until the fifteenth century that the symbols that we are familiar with today first took form in Europe. However, the history of these numbers and their development goes back hundreds of years. One important source of information on this topic is the writer al-Biruni, whose picture is shown in figure 1.[2] Al-Biruni, who was born in modern day Uzbekistan, had visited India on several occasions and made comments on the Indian number system. When we look at the origins of the numbers that al-Biruni encountered, we have to go back to the third century BCE to explore their origins. It is then that the Brahmi numerals were being used.

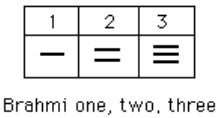

The Brahmi numerals were more complicated than those used in our own modern system. They had separate symbols for the numbers [latex]1[/latex] through [latex]9[/latex], as well as distinct symbols for [latex]10[/latex], [latex]100[/latex], [latex]1000[/latex],…, also for [latex]20[/latex], [latex]30[/latex], [latex]40[/latex],…, and others for [latex]200[/latex], [latex]300[/latex], [latex]400[/latex], …, [latex]900[/latex]. The Brahmi symbols for [latex]1[/latex], [latex]2[/latex], and [latex]3[/latex] are shown below.[3]

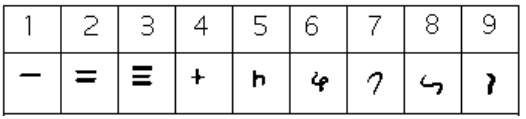

These numerals were used all the way up to the fourth century CE, with variations through time and geographic location. For example, in the first century CE, one particular set of Brahmi numerals took on the following form:[4]

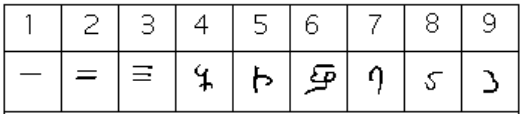

From the fourth century on, you can actually trace several different paths that the Brahmi numerals took to get to different points and incarnations. One of those paths led to our current numeral system, and went through what are called the Gupta numerals. The Gupta numerals were prominent during a time ruled by the Gupta dynasty and were spread throughout that empire as they conquered lands during the fourth through sixth centuries. They have the following form:[5]

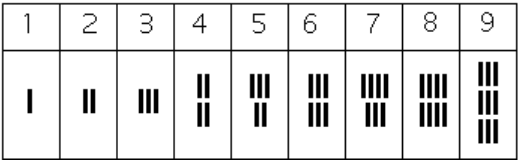

How the numbers got to their Gupta form is open to considerable debate. Many possible hypotheses have been offered, most of which boil down to two basic types.[6] The first type of hypothesis states that the numerals came from the initial letters of the names of the numbers. This is not uncommon the Greek numerals developed in this manner. The second type of hypothesis states that they were derived from some earlier number system. However, there are other hypotheses that are offered, one of which is by the researcher Ifrah. His theory is that there were originally nine numerals, each represented by a corresponding number of vertical lines. One possibility is this:[7]

Because these symbols would have taken a lot of time to write, they eventually evolved into cursive symbols that could be written more quickly. If we compare these to the Gupta numerals above, we can try to see how that evolutionary process might have taken place, but our imagination would be just about all we would have to depend upon since we do not know exactly how the process unfolded.

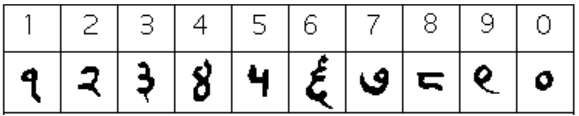

The Gupta numerals eventually evolved into another form of numerals called the Nagari numerals, and these continued to evolve until the eleventh century, at which time they looked like this:[8]

Note that by this time, the symbol for [latex]0[/latex] has appeared! The Mayans in the Americas had a symbol for zero long before this, however.

These numerals were adopted by the Arabs, most likely in the eighth century during Islamic incursions into the northern part of India.[9] It is believed that the Arabs were instrumental in spreading them to other parts of the world, including Spain (see below).

Other examples of variations up to the eleventh century include:[10]

Finally, figure 14[11] shows various forms of these numerals as they developed and eventually converged to the fifteenth century in Europe.

Hindu—Arabic Numbers

You can view the transcript for “The Fascinating History of Arabic Numerals (Modern Day Numbers!)” here (opens in new window).

You can view the transcript for “A brief history of numerical systems – Alessandra King” here (opens in new window).

You can view the transcript for “The Origin of Numbers” here (opens in new window).

- "https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Indian_numerals/" ↵

- "http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Mathematicians/Al-Biruni.html" ↵

- "https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Indian_numerals/" ↵

- "https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Indian_numerals/" ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Katz, page 230 ↵

- Burton, David M., History of Mathematics, An Introduction, p. 254–255 ↵

- Katz, page 231. ↵