- Discuss happiness and the factors that can increase it

- Describe the field of positive psychology

- Give examples of flow

Although the study of stress and how it affects us physically and psychologically is fascinating, it is—admittedly—somewhat of a grim topic. Psychology is also interested in the study of a more upbeat and encouraging approach to human affairs—the quest for happiness.

Happiness

America’s founders declared that its citizens have an unalienable right to pursue happiness. But what is happiness? When asked to define the term, people emphasize different aspects of this elusive state. Indeed, happiness is somewhat ambiguous and can be defined from different perspectives (Martin, 2012). Some people, especially those who are highly committed to their religious faith, view happiness in ways that emphasize virtuosity, reverence, and enlightened spirituality. Others see happiness as primarily contentment—the inner peace and joy that come from deep satisfaction with one’s surroundings, relationships with others, accomplishments, and oneself. Still others view happiness mainly as pleasurable engagement with their personal environment—having a career and hobbies that are engaging, meaningful, rewarding, and exciting. These differences, of course, are merely differences in emphasis. Most people would probably agree that each of these views, in some respects, captures the essence of happiness.

Elements of Happiness

Some psychologists have suggested that happiness consists of three distinct elements: the pleasant life, the good life, and the meaningful life, as shown in Figure 1 (Seligman, 2002; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005).

The elements of happiness

- The pleasant life is realized through the attainment of day-to-day pleasures that add fun, joy, and excitement to our lives. For example, evening walks along the beach and a fulfilling sex life can enhance our daily pleasure and contribute to the pleasant life.

- The good life is achieved through identifying our unique skills and abilities and engaging these talents to enrich our lives; those who achieve the good life often find themselves absorbed in their work or their recreational pursuits.

- The meaningful life involves a deep sense of fulfillment that comes from using our talents in the service of the greater good: in ways that benefit the lives of others or that make the world a better place.

In general, the happiest people tend to be those who pursue the full life—they orient their pursuits toward all three elements (Seligman et al., 2005).

For practical purposes, a precise definition of happiness might incorporate each of these elements:

happiness

Happiness is an enduring state of mind consisting of joy, contentment, and other positive emotions, plus the sense that one’s life has meaning and value (Lyubomirsky, 2001).

The definition implies that happiness is a long-term state—what is often characterized as subjective well-being—rather than merely a transient positive mood we all experience from time to time. It is this enduring happiness that has captured the interests of psychologists and other social scientists.

The study of happiness has grown dramatically in the last three decades (Diener, 2013). One of the most basic questions that happiness investigators routinely examine is this: How happy are people in general? The average person in the world tends to be relatively happy and tends to indicate experiencing more positive feelings than negative feelings (Diener, Ng, Harter, & Arora, 2010). When asked to evaluate their current lives on a scale ranging from 0 to 10 (with 0 representing “worst possible life” and 10 representing “best possible life”), people in more than 150 countries surveyed from 2010–2012 reported an average score of 5.2. People who live in North America, Australia, and New Zealand reported the highest average score at 7.1, whereas those living Sub-Saharan Africa reported the lowest average score at 4.6 (Helliwell, Layard, & Sachs, 2013). Worldwide, the five happiest countries are Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Sweden; the United States is ranked 17th happiest (Figure 2) (Helliwell et al., 2013).

Several years ago, a Gallup survey of more than 1,000 U.S. adults found that 52% reported that they were “very happy.” In addition, more than 8 in 10 indicated that they were “very satisfied” with their lives (Carroll, 2007). However, a recent poll found that only 42% of American adults report being “very happy.” The groups that show the greatest declines in happiness are people of color, those who have not completed a college education, and those who politically identify as Democrats or independents (McCarthy, 2020). These results suggest that challenging economic conditions may be related to declines in happiness. Of course, this interpretation implies that happiness is closely tied to one’s finances. But, is it? What factors influence happiness?

The global average life evaluations during the COVID-19 years of 2020-2022 remained as high as those in the pre-pandemic years of 2017-2019, indicating remarkable resilience. According to the World Happiness Report, Finland maintained its position as the happiest country for the sixth consecutive year. Lithuania saw significant improvement, entering the top twenty countries. On the other hand, war-torn Afghanistan and Lebanon remained the unhappiest countries, with much lower average life evaluations than the top countries.

Trust and social support played a crucial role in supporting happiness during crises, as evidenced by lower death rates in countries with effective COVID-19 strategies, increased benevolence globally, and the prevalence of positive social connections. These factors contributed to the resilience of life evaluations amidst the challenges of the pandemic.

Subjective Well-Being

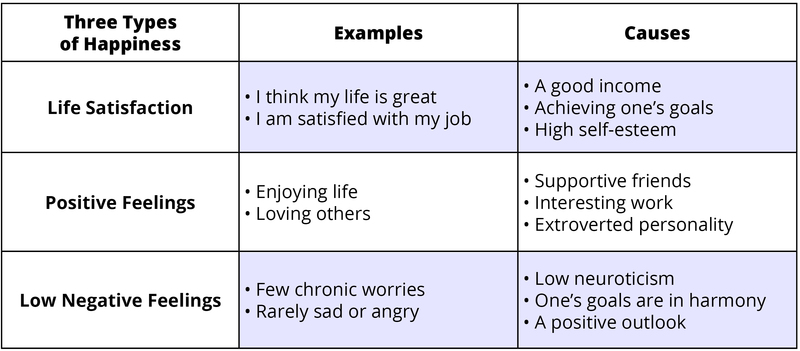

Another way that researchers define happiness is by examining high life satisfaction, frequent positive feelings, and infrequent negative feelings (Diener, 1984). “Subjective well-being” is the label given by scientists to the various forms of happiness taken together. Although there are additional forms of SWB, the three in the table below have been studied extensively. The table also shows that the causes of the different types of happiness can be somewhat different.

You can see in the table that there are different causes of happiness, and that these causes are not identical for the various types of SWB. Therefore, there is no single key, no magic wand—high SWB is achieved by combining several different important elements (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2008). Thus, people who promise to know the key to happiness are oversimplifying.

Factors Connected to Happiness

What really makes people happy? What factors contribute to sustained joy and contentment? Is it money, attractiveness, material possessions, a rewarding occupation, or a satisfying relationship? Extensive research over the years has examined this question. Although it is important to point out that much of this work has been correlational, many of the key findings (some of which may surprise you) are summarized below.

- Family and social relationships are correlated with happiness (Diener et al., 1999; Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005; Myers, 2000).

- The 2025 World Happiness Report found that people living in households with 4-5 members report the highest life satisfaction.[1]

- On average, partnered/married people report higher life satisfaction, especially when relationship quality is high; effects vary by person and culture.[2]

- Happy individuals have more friends, high-quality social relationships, and strong social support networks (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

- Happy people have frequent contact with friends (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2000; Song et al., 2023).[3]

- Money can buy happiness up to a certain point (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2002; Diener, Oishi, & Ryan, 2013).

- For years, psychologists cited a “$75,000 plateau” based on Kahneman & Deaton (2010) research, claiming that life evaluation (how you judge your life overall) continues to rise with income until having your basic needs met at $75,000. A 2023 joint reanalysis by Kahneman & Killingsworth found that for most, emotional well‑being keeps increasing with income; only a small minority of the least happy people did increasing income no longer impact their happiness (after $100,000) (Killingsworth, 2021; Kahneman & Killingsworth, 2023).

- Wealthy individuals tend to be slightly happier than poor individuals, but the association is weaker within countries (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2002).

- Per capita GDP is associated with happiness levels (Helliwell et al., 2024), though changes in GDP have little relationship with changes in happiness (Diener, Tay, & Oishi, 2013). This Easterlin Paradox, named after economist Richard Easterlin, who first documented it in 1974, shows that economic growth doesn’t increase average happiness (Easterlin & O’Connor, 2020/2022).

- Higher incomes may impair people’s ability to savor and enjoy small pleasures (Kahneman, 2011; Quoidbach et al., 2010). More recent reviews found that high income often coexists with time pressure, but time affluence (having discretionary time) predicts higher well‑being (Kaufman et al., 2020; Whillans et al., 2021; Kouchaki et al., 2020).

- Education and meaningful employment are correlated with happiness (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Education’s link to life satisfaction is small and often mediated by labor‑market outcomes; however, education strongly predicts health and longevity (World Happiness Report, 2024). There is still little evidence that general intelligence has a strong, direct link to life satisfaction. (Diener et al., 1999; Araki, 2021).

- Religiosity correlates with happiness, especially in nations with difficult living conditions (Hackney & Sanders, 2003; Diener, Tay, & Myers, 2011). Recent studies shows that becoming more religious, however, does not necessarily raise one’s life satisfaction, so cultural context may be an important part of the association between religion and well-being (Joshanloo, 2021; Zheng & Xu, 2023).

- A 2025 U.S. study found that religious attendance, perceptions of divine control, and secure attachment to God were associated with greater happiness, with benefits being stronger for those with lower education and income.[4]

- Culture influences happiness by determining which characteristics are valued (Diener, 2012). In cultures that prize certain traits or achievements, individuals who possess those characteristics tend to be happier. For instance, self-esteem predicts life satisfaction more strongly in individualistic cultures like the United States, where independence and personal achievement are emphasized (Diener, Diener, & Diener, 1995). Similarly, extraverted individuals report greater happiness in cultures where extraversion is valued and rewarded (Fulmer et al., 2010).

- Engaging in prosocial behavior—helping others, volunteering, and performing acts of kindness—is positively associated with happiness and well-being (Hui et al., 2020; Schindler et al., 2021). Meta-analyses reveal small but consistent improvements in subjective well-being from these behaviors, demonstrating that “doing good feels good.” This benevolence effect appears across cultures and is increasingly recognized as both a coping mechanism and a pathway to personal happiness.

What Doesn’t Predict Happiness?

Understanding what doesn’t predict happiness can be just as informative as knowing what does, as it challenges common assumptions about the sources of well-being.

Although people tend to believe that parenthood is central to a meaningful and fulfilling life, studies across many industrialized nations reveal a more complex picture. Parents often report lower levels of happiness than childless adults in countries with limited family support, but in nations with strong work-family reconciliation policies—such as paid parental leave, subsidized childcare, and flexible work arrangements—parents report happiness levels comparable to or even higher than non-parents.[5]

The relationship between parenthood and happiness depends heavily on economic support systems, the age of children, and the distinction between moment-to-moment emotions (which may be more negative during stressful childcare tasks) and overall life satisfaction (which incorporates meaning and purpose beyond immediate pleasure).

Similarly, objective physical attractiveness shows only a weak correlation with happiness (Diener, Wolsic, & Fujita, 1995). Interestingly, perceived attractiveness—how attractive you believe you are—predicts happiness more strongly than objective ratings by others, illustrating a broader principle: subjective perceptions often matter more than objective circumstances.

Several other factors show surprisingly weak relationships with happiness, revealing common misconceptions about well-being. Age, gender, and intelligence (IQ) all explain relatively little variation in happiness once basic needs are met (Diener et al., 1999).

Geographic location within a country (urban vs. rural, different regions) typically shows weak associations with happiness after controlling for factors like income and social connections.

These findings matter because they reveal how cultural narratives mislead us—society suggests that having children, being attractive, or being highly intelligent will guarantee happiness, but the data don’t strongly support these beliefs.

- Rojas, M., Martínez, L., Leyva Parra, G., Castellanos, R., & Tarragona, M. (2025). Living with others: How household size and family bonds relate to happiness. In J. F. Helliwell, R. Layard, J. D. Sachs, J.-E. De Neve, L. B. Aknin, & S. Wang (Eds.), World happiness report 2025. https://doi.org/10.18724/whr-5xep-q992 ↵

- Bühler, J. L., Krauss, S., & Orth, U. (2021, December 20). Development of Relationship Satisfaction Across the Life Span: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bul0000342 ↵

- Song, I., Kwon, J. W., & Jeon, S. M. (2023). The relative importance of friendship to happiness increases with age. PloS one, 18(7), e0288095. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288095 ↵

- Upenieks L. (2025). Are Religious People Any Happier? Probing the Divine Relationship, Organizational Religiosity and the Role of Education and Income in the United States. Journal of religion and health, 64(6), 4635–4660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-025-02295-6 ↵

- Glass J, Simon RW, Andersson MA. Parenthood and Happiness: Effects of Work-Family Reconciliation Policies in 22 OECD Countries. AJS. 2016 Nov;122(3):886-929. doi: 10.1086/688892. PMID: 28082749; PMCID: PMC5222535. ↵