Stress and the Body

If the reactions that compose the stress response are chronic or if they frequently exceed normal ranges, they can lead to cumulative wear and tear on the body, in much the same way that running your air conditioner on full blast all summer will eventually cause wear and tear on it. For example, the high blood pressure that a person under considerable job strain experiences might eventually take a toll on their heart and set the stage for a heart attack or heart failure. Also, someone exposed to high levels of the stress hormone cortisol might become vulnerable to infection or disease because of weakened immune system functioning (McEwen, 1998).

psychophysiological disorders

Physical disorders or diseases whose symptoms are brought about or worsened by stress and emotional factors are called psychophysiological disorders. The physical symptoms of psychophysiological disorders are real and they can be produced or exacerbated by psychological factors (hence the psycho and physiological in psychophysiological).

A list of frequently encountered psychophysiological disorders is provided in Table 1.

| Type of Psychophysiological Disorder | Examples |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | hypertension, coronary heart disease |

| Gastrointestinal | irritable bowel syndrome |

| Respiratory | asthma, allergy |

| Musculoskeletal | low back pain, tension headaches |

| Skin | acne, eczema, psoriasis |

Friedman and Booth-Kewley (1987) statistically reviewed 101 studies to examine the link between personality and illness. They proposed the existence of disease-prone personality characteristics, including depression, anger/hostility, and anxiety. Indeed, a study of over 61,000 Norwegians identified depression as a risk factor for all major disease-related causes of death (Mykletun et al., 2007). In addition, neuroticism—a personality trait that reflects how anxious, moody, and sad one is—has been identified as a risk factor for chronic health problems and mortality (Ploubidis & Grundy, 2009).

Before we discuss two kinds of psychophysiological disorders about which a great deal is known: cardiovascular disorders and asthma, it is necessary to turn our attention to a discussion of the immune system—one of the major pathways through which stress and emotional factors can lead to illness and disease.

Immune System

In a sense, the immune system is the body’s surveillance system. It consists of a variety of structures, cells, and mechanisms that serve to protect the body from invading microorganisms that can harm or damage the body’s tissues and organs. When the immune system is working as it should, it keeps us healthy and disease free by eliminating bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances that have entered the body (Everly & Lating, 2002).

Autoimmune Disease

In addition, the immune system may sometimes break down and be unable to do its job.

Stressors and Immune Function

Psychoneuroimmunology was coined in 1981 to describe the study of connections between the brain, endocrine system, and immune system (Zacharie, 2009). Evidence from classical conditioning studies in animals supports the connection between the brain and the immune system (Everly & Lating, 2002). These studies demonstrated that immune responses can be conditioned, suggesting the potential for psychological factors, including stress, to affect immunity.

Numerous studies involving large participant samples have explored the effects of various stressors on immune function. These stressors include public speaking, exams, unemployment, marital discord, caregiving, and exposure to harsh environments (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2002; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004). The findings consistently reveal that many types of stressors are associated with weakened immune functioning.

The physiological connection between the brain and the immune system is evident. The sympathetic nervous system innervates immune organs, and stress hormones released during hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation can adversely affect immune function by inhibiting lymphocyte production (Maier et al., 1994; Everly & Lating, 2002).

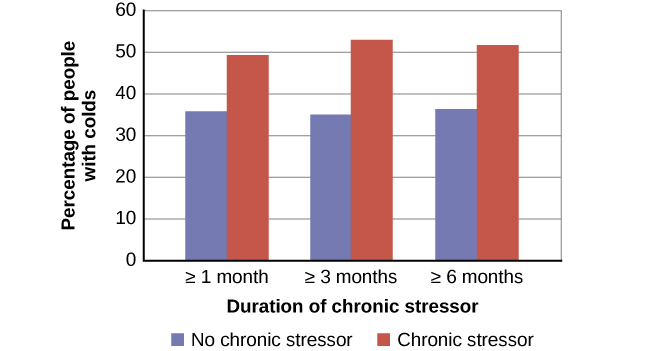

Studies investigating the link between stress and impaired immune function have exposed volunteers to viruses. For example, one study found that participants reporting chronic stressors, particularly work- or relationship-related difficulties, were more susceptible to developing colds compared to those without chronic stressors (Cohen et al., 1998), as seen in Figure 1.

In another study, older volunteers were given an influenza virus vaccination. Compared to controls, those who were caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease (and thus were under chronic stress) showed poorer antibody response following the vaccination (Kiecolt-Glaser, Glaser, Gravenstein, Malarkey, & Sheridan, 1996).

Other studies have demonstrated that stress slows down wound healing by impairing immune responses important to wound repair (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005). In one study, for example, skin blisters were induced on the forearm. Subjects who reported higher levels of stress produced lower levels of immune proteins necessary for wound healing (Glaser et al., 1999). Stress, then, is not so much the sword that kills the knight, so to speak; rather, it’s the sword that breaks the knight’s shield, and your immune system is that shield.

Stress and Aging: A Tale of Telomeres

Have you ever wondered why people who are stressed often seem to have a haggard look about them? A pioneering study from 2004 suggests that the reason is that stress can actually accelerate the cell biology of aging.

Stress, it seems, can shorten telomeres, which are segments of DNA that protect the ends of chromosomes. Shortened telomeres can inhibit or block cell division, which includes the growth and proliferation of new cells, thereby leading to more rapid aging (Sapolsky, 2004). In the study, researchers compared telomere lengths in the white blood cells in mothers of chronically ill children to those of mothers of healthy children (Epel et al., 2004). Mothers of chronically ill children would be expected to experience more stress than would mothers of healthy children. The longer a mother had spent caring for her ill child, the shorter her telomeres (the correlation between years of caregiving and telomere length was r = -.40). In addition, higher levels of perceived stress were negatively correlated with telomere size (r = -.31). These researchers also found that the average telomere length of the most stressed mothers, compared to the least stressed, was similar to what you would find in people who were 9–17 years older than they were on average.

Numerous other studies have continued to find associations between stress and eroded telomeres (Blackburn & Epel, 2012). Some studies have even demonstrated that stress can begin to erode telomeres in childhood and perhaps even before children are born. For example, childhood exposure to violence (e.g., maternal domestic violence, bullying victimization, and physical maltreatment) was found in one study to accelerate telomere erosion from ages 5 to 10 (Shalev et al., 2013). Another study reported that young adults whose mothers had experienced severe stress during their pregnancy had shorter telomeres than did those whose mothers had stress-free and uneventful pregnancies (Entringer et al., 2011). Further, the corrosive effects of childhood stress on telomeres can extend into young adulthood. In an investigation of over 4,000 U.K. women ages 41–80, adverse experiences during childhood (e.g., physical abuse, being sent away from home, and parent divorce) were associated with shortened telomere length (Surtees et al., 2010), and telomere size decreased as the amount of experienced adversity increased (Figure 2).

Efforts to dissect the precise cellular and physiological mechanisms linking short telomeres to stress and disease are currently underway. For the time being, telomeres provide us with yet another reminder that stress, especially during early life, can be just as harmful to our health as smoking or fast food (Blackburn & Epel, 2012).