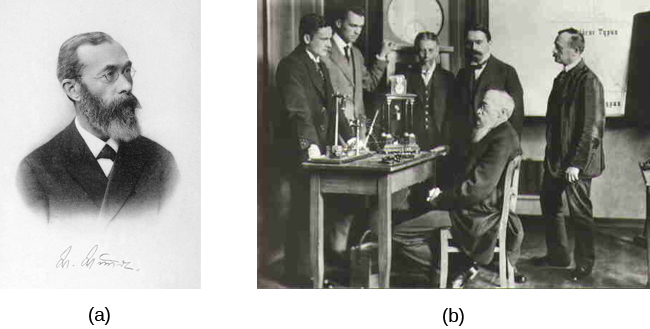

Wilhelm Wundt

German physician and philosopher Wilhelm Wundt (pronounced “VIL-helm Voont”) (1832–1920) is often recognized as the founder of modern psychology. He argued that psychology could be studied scientifically and built the first laboratory for psychological research at the University of Leipzig in 1879, an event widely recognized as the formal beginning of psychology as a science.

The world quickly embraced Wilhelm Wundt’s new science of psychology. Wundt attracted students from around the world to study the new experimental psychology and work in his lab. His students were trained in introspection, a method where they would provide in-depth self-reports about their reactions to different stimuli.

Introspection, or “internal perception” as Wundt called it, was used to study the human mind like any other observable natural phenomenon. It aimed to identify the elements of consciousness, but due to its subjective nature, results often varied between individuals.

Wundt also pioneered mental chronometry, measuring how quickly people reacted to stimuli like lights or sounds. His work demonstrated that the mind could be studied empirically, sparking international interest.

Four years after Wundt’s lab was established in 1879, G. Stanley Hall set up the first American psychology lab.

Edward Titchener

Edward Bradford Titchener, a student of Wundt’s, is mainly responsible for introducing Wundt’s version of psychology, known as structuralism, to America. Structuralism focuses on understanding the contents of the mind.

structuralism

Structuralism aims to break down conscious experiences into their basic elements or component parts. Structuralists wanted to identify the basic structures that could explain behavior, similar to the periodic table in chemistry or fundamental laws in physics.

Structuralists focused on sensation and perception. For instance, a structuralist studying someone viewing a flower would identify the raw sensory data—color, shape, texture—rather than naming the object. Titchener enforced strict rules for introspection: subjects could describe features of objects (like length or color of a pencil) but not the object’s name, because that did not describe the raw data of what the subject was experiencing.

The Spread of Experimental Psychology

Experimental psychology spread rather rapidly throughout North America. By 1900, there were more than 40 laboratories in the United States and Canada (Benjamin, 2000). Psychology in America was organized early with the establishment of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1892.

Titchener felt that this new organization did not adequately represent the interests of experimental psychology, so, in 1904, he organized a group of colleagues to create what is now known as the Society of Experimental Psychologists (Goodwin, 1985). The group met annually to discuss research in experimental psychology. Reflecting the times, women researchers were not invited (or welcome) to participate.

Debates over balancing the scientific study of psychology with its practical applications began in this period and continue today. To emphasize the science side, the Association for Psychological Science (APS) was founded in 1988.

Breaking Gender Barriers

Though women were denied access to most psychology labs, it should be noted that Titchener’s first doctoral student was a woman, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939).

Despite many obstacles, in 1894, Washburn became the first woman in America to earn a Ph.D. in psychology and, in 1921, only the second woman to be elected president of the American Psychological Association (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987). Though she was well-versed in structuralism, she pulled from all schools of thought, and came to focus on animal behavior and cognition.

Washburn wrote The Animal Mind: A Textbook of Comparative Psychology, which became the standard in the field for over 20 years. She was a professor at Vassar College (then a women’s college) for most of her career.