The Stanford Prison Experiment

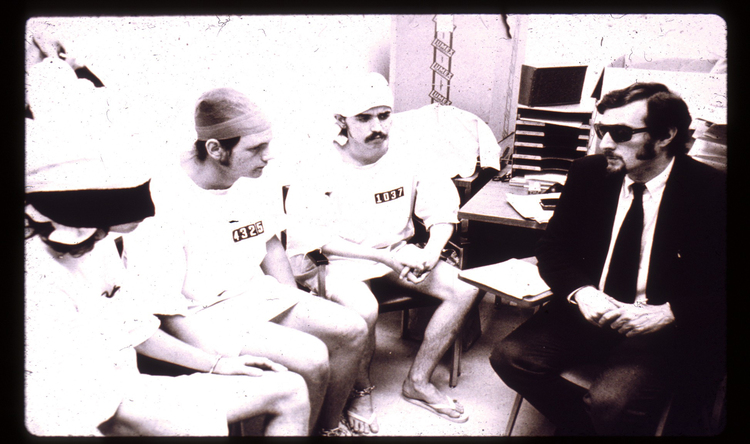

In the summer of 1971, a California newspaper ad sought male volunteers to study the psychological impacts of prison life. From numerous applicants, researchers selected 24 healthy college students—mostly middle-class and White males. Paid $15 per day, participants were randomly assigned roles as either prisoners or guards in a makeshift “prison” located in Stanford University’s psychology building. The study was planned to last two weeks.

Rapid Role Adoption

Participants immersed themselves in their assigned roles with alarming speed and intensity. Guards engaged in increasingly sadistic behaviors, depriving prisoners of sleep and privacy. Prisoners exhibited heightened anxiety and hopelessness, tolerating the guards’ abuse. Due to this rapid behavioral degradation, the study was terminated after only six days.

Psychologist Philip Zimbardo, who led the study, concluded that participants were fulfilling their social roles. Social norms—expectations of appropriate behavior in social settings—require guards to be authoritarian and prisoners to be submissive. When prisoners rebelled by throwing pillows and trashing their cells, they violated these norms. Guards responded by demeaning prisoners with push-ups and removing their privacy. Zimbardo used the experiment as evidence for why good people do evil things.

Questionable Findings: A Second Look

The Stanford Prison Experiment’s findings have been heavily criticized, and Zimbardo has faced accusations of using unscientific practices. Critics raise several concerns:

- Demand Characteristics: Participants may have exaggerated their behaviors to “please” the experimenter or re-enacted behaviors they had seen in media. One guard later admitted behaving aggressively so “the researchers would have something to work with.”

- Experimenter Influence: Zimbardo instructed guards to exert psychological control over prisoners, directly shaping their behavior rather than observing naturally occurring responses.

- The Hawthorne Effect: Knowing they were being watched may have altered participants’ behavior. Guards may have acted more aggressively when supervisors failed to intervene, interpreting this as tacit approval.

- Methodological Flaws: The study suffered from a small, unrepresentative sample. Additionally, recruitment flyers explicitly mentioned “prison life,” attracting participants already interested in this topic and potentially biasing results.

- Failed Replication: The experiment’s results have never been successfully replicated, raising serious questions about their validity and generalizability.