Good Relationships Correlate With Better Health

An impressive amount of research from psychology and medicine supports the claim that having a strong social support network— supportive friends and family—is associated with maintaining both physical and psychological health and recovering quickly and effectively from physical and psychological problems.

The goal of scientific psychology is to understand the deep underlying causes of psychological and behavioral factors. Evidence that there is an association between health and social support is the beginning—not the end—of scientific investigation. We want to know why such a relationship exists.

Correlations can identify interesting relationships (e.g., there is a positive correlation between a person’s amount of social support and success in recovering from physical and psychological problems), but they usually cannot provide strong evidence for why that relationship exists. That is the job of experiments.

When you design an experiment, you must often create a very specific situation to test and explore your ideas. We have been talking in grand terms about “social support networks” and “mental and physical health,” but individual experiments typically cannot work on such a broad scale. Instead, the experimenter tries to find a single simple type of social support that can be manipulated in the laboratory and a single simple element of health that can be measured and studied in the laboratory. One disadvantage of this sharp focus on a specific situation in experiments is that a single experiment—even a single set of related experiments—is unlikely to fully identify the causes we are looking for. Experimental evidence typically accumulates slowly, over long periods of time, filled with apparent contradictions that can take time and effort to sort out.

We are going to look at two experiments from different research teams that take a similar approach to trying to understand if social contact influences a health-related experience—in this case, pain—and how such an influence might work (i.e., what might be the causal mechanisms?).

Experiment 1: Love and Pain

Sarah L. Master and her colleagues[1] conducted a simple experiment that they published in 2009. Their subjects were healthy college students who volunteered to participate in an experiment that tested the idea that contact with a romantic partner can reduce our experience of pain.

Participants

Master and her colleagues recruited heterosexual couples to participate in their study.[2] The women were the actual subjects in the study. Their male partners participated as part of the experimental manipulation. The participants were in stable, long-term (defined here as longer than 6 months) relationships.

Pain Induction

Before the experiment began, each woman was tested to find her personal pain experiences for thermal stimulation (i.e., heat), which was produced by a medical device called a thermode. Different people experience and report pain very differently, so calibration of the thermal stimulation to the individual’s pain experience was essential. The thermal stimulation during the experiment was adjusted to the point at which the subject reported a “moderate” level of discomfort (10 on a 20-point discomfort scale) when the heat was applied. This means that different people experienced different objective amounts of heat, while the subjective “discomfort” should have been approximately the same. The heat stimulus was delivered to the soft inside of the right forearm[3], and each one lasted for 6 seconds.

Experimental Conditions

There were seven conditions in the experiment.

In three of the conditions, the woman held something in her hand as she experienced the painful thermal stimulation. She held either:

- The hand of her partner (who sat behind a curtain, and—except for his hand—was not visible).

- The hand of a male stranger (who was also behind a curtain).

- An object: a squeeze ball.

In three other conditions, the woman looked at a picture on a computer screen in front of her. She saw either:

- A picture of her partner taken while the woman was being prepared for the experiment.

- A picture of a male stranger (similar age and matched for ethnicity with the woman’s partner).

- An object: a picture of a chair.

One control (or baseline) condition:

- The woman looked at a fixation cross on the computer screen.

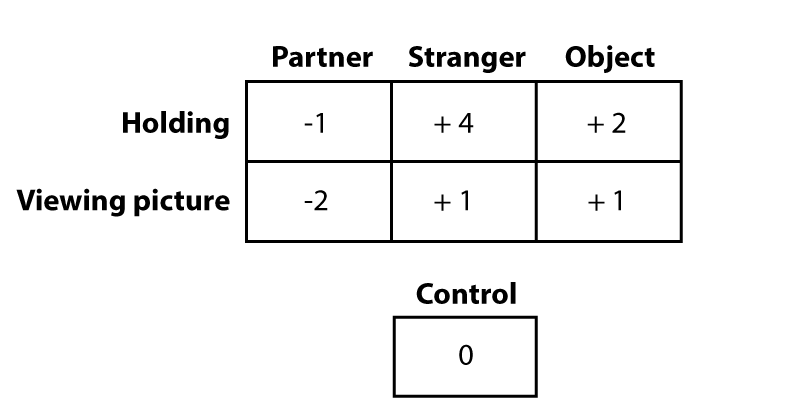

The figure below shows summarizes the organization (technically, the “design”) of the experiment.

Procedure

The woman received twelve thermal stimulations in each condition. The order of presentation of conditions was randomized for each woman.[4] There was a 20-second break between stimulations. After each stimulation, the subject rated how “uncomfortable” the stimulus was on a 21-point scale.

Results

To take account of individual differences, the control condition (i.e., looking at a fixation cross on a computer screen) the experimenters found the difference between each person’s average control condition unpleasantness rating and her rating for each condition. For example, imagine that one participant has the following average “unpleasantness” ratings (on the 21-point scale):[5]

The control rating (10) is then subtracted from each of the treatment ratings. This becomes the score that is analyzed (called a “difference score”). This method allows each woman to have a different general pain level (in the example, it is “10” but another person might have “6” or “12” as her average). The difference score looks at each person’s change from her personal baseline under the various conditions.

For the difference scores, a positive number means that the experience in that condition was more painful than it was in the control condition. A negative number means that the experience in that condition was less painful than it was in the control condition. The exact number used indicates how much more or less painful the experience was.

Try It

Before we show you the actual results of the experiment, we’d like you to predict what you think happened in this experiment. Use the figure below. The zero baseline is the control condition. Your predictions are about the six treatment conditions. You can click and drag on a bar to move the bar up, if you think that condition was more painful for the subject than the baseline control. And you can move a bar down if you think that condition was less painful than the baseline control condition.

The initial screen below shows all six of the treatment conditions as a tiny bit more painful than the baseline control. Make your predictions based on your own theory about the possible positive or negative effects of holding the hands of a person you love or of a stranger, or looking at a picture of a person you love or a stranger while you are in pain. Remember that zero baseline control is still very painful, so zero does not mean that there is no pain.

Conclusions

These results suggest that there is something special about a person we love—or at least someone we like. Dr. Master noted that looking at a picture of a loved one may be slightly more beneficial than holding his hand, though this difference did not quite reach statistical significance. Holding a stranger’s hand exaggerated the pain experience by a considerable amount, so it is clear that (in the context of this experiment) human contact alone is not enough to relieve pain.

Dr. Master makes a practical suggestion: If you are going to have a painful medical procedure, bringing a picture of someone you love may be helpful in reducing the pain. In fact, based on a comparison of the hand-holding and picture-viewing conditions, you may actually be better off bringing a picture than bringing the actual person to the painful procedure.

Here is her final conclusion: “In sum, these findings challenge the notion that the beneficial effects of social support come solely from supportive social interactions and suggest that simple reminders of loved ones may be sufficient to engender feelings of support.” If you think back to the introduction to this activity, we said that our goal was to find out how and why social support leads to better health outcomes. As we cautioned you, this experiment doesn’t even come close to answering that question. However, it does take us one little step in the right direction, suggesting that “social support” may be more complicated than just having people near us or even a group of friends. “Social support” may involve triggering certain cognitive (mental) processes, such as memories and emotions, that are associated with strong positive relationships. That is for future research to clarify.

- Sarah Master was then a graduate student at UCLA and is now a research associate with a Ph.D. at UCLA. Several of her co-authors are major figures in the field of health psychology. For example, co-author Shelly Taylor is one of the founders of the field of health psychology. ↵

- Researchers must often decide between restricting the characteristics of their subjects to simplify factors influencing the results versus opening the experiment to a broader range of subjects to improve generalizability and representativeness. Restriction of the participants in this study to heterosexual couples does not imply that couples with other gender identities or sexual orientations are either unimportant or uninteresting. ↵

- Alternating among three different locations on different trials. ↵

- The randomization procedure was a bit more complicated than this explanation suggests. See the original paper if you want to know exactly what they did. ↵

- As any doctor will tell you, getting a valid and reliable rating of pain is notoriously difficult. Master and her colleagues used a scale (the Gracely Box Scale) that is widely used in research and has been extensively validated. ↵