Persuasion: Changing Attitudes Through Communication

Cognitive dissonance can lead us to change our attitudes, behaviors, and/or cognitions to make them consistent. However, cognitive dissonance is not the only force that motivates attitude change. We are also influenced by persuasion—deliberate attempts by others to change what we think and how we behave.

persuasion

Persuasion is the process of changing our attitude toward something based on some kind of communication. Much of the persuasion we experience comes from outside forces.

How do people convince others to change their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors? What communications do you receive that attempt to persuade you to change your attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors?

How to Change an Attitude: The Yale Attitude Change Approach

Persuasion has been one of the most heavily researched topics in social psychology. During World War II, Carl Hovland studied how persuasive messages could motivate soldiers, then continued this work at Yale University. His team developed the Yale attitude change approach, which explains how three elements—the source, the message, and the audience—shape whether a message succeeds.

Modern research still supports these categories, even as communication channels have evolved.

#1: The Source

The source of a message matters. Hovland’s early research showed that persuasive messages are more effective when they come from sources that are:

- Credible

- Trustworthy

- Physically attractive or otherwise likable

Celebrities, experts, influencers, and charismatic leaders all benefit from these features.

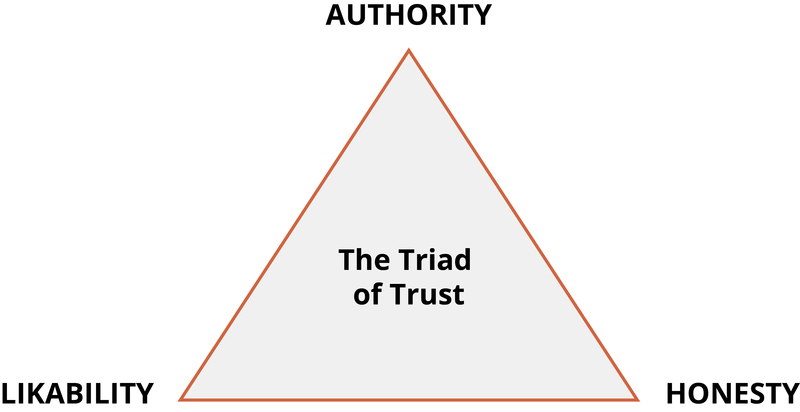

The Source and the Triad of Trustworthiness

Effective persuasion requires trusting the source of the communication. Studies have identified three characteristics that lead to trust: perceived authority, honesty, and likability.

Authority: we have a tendency to trust those viewed to be in authority positions, though this can be problematic for several reasons. First, even if the source of the message is a legitimate, well-intentioned authority, they may not always be correct. Second, when respect for authority becomes mindless, expertise in one domain may be confused with expertise in general. To assume there is credibility when a successful actor promotes a cold remedy, or when a psychology professor offers his views about politics, can lead to problems. Third, the authority may not be legitimate. It is not difficult to fake a college degree or professional credential or to buy an official-looking badge or uniform.

Honesty: If a person or company is viewed as honest, they can be easily trusted. This becomes a mental shortcut to help us sift through large volumes of information, signaling that we are in safe territory.

Likability: More than any single quality, we trust people we like. The mix of qualities that make a person likable is complex and often does not generalize from one situation to another. One clear finding, however, is that physically attractive people tend to be liked more. In fact, we prefer them to a disturbing extent: various studies have shown we perceive attractive people as smarter, kinder, stronger, more successful, more socially skilled, better poised, better adjusted, more exciting, more nurturing, and, most important, of higher moral character. All of this is based on no other information than their physical appearance (e.g., Dion, Berscheid, & Walster, 1972).

Contemporary studies show that digital authority (e.g., follower counts, verification badges, professional branding) can also increase perceived credibility, even when it is not tied to actual expertise. This makes source evaluation especially important in online spaces.

#2: The Message

Persuasion also depends on what the message says and how it is delivered. Factors that influence message effectiveness include:

- Subtlety – Messages that invite reflection rather than pressure may be more persuasive.

- Sidedness – Presenting both sides of an argument (then explaining why one is stronger) increases credibility, especially among skeptical audiences.

- Timing – When two messages are delivered back-to-back, the first one tends to be more persuasive—this is called the primacy effect. However, if there is a delay between the first message and the decision, the last message presented tends to be more persuasive—this is the recency effect.

Messages connecting to a person’s identity (e.g., “I am the kind of person who…”) can be powerful motivators of change, especially when the message aligns with group norms or values. For example, “I am a voter,” is more powerful than “Be a voter.”[1]

#3: The Audience

Finally, persuasion depends on who is receiving the message. Important audience characteristics include:

- Attention: To be persuaded, audience members must be paying attention (Albarracín & Wyer, 2001; Festinger & Maccoby, 1964). Distracted audiences are less likely to be influenced.

- Intelligence: People with lower intelligence are more easily persuaded than those with higher intelligence, likely because they are less able to critically evaluate arguments.

- Self-esteem: People with moderate self-esteem are more easily persuaded than those with very high or very low self-esteem (Rhodes & Wood, 1992). Those with high self-esteem are confident in their existing views, while those with very low self-esteem may be too defensive to accept persuasive messages.

- Age: Younger adults aged 18–25 are more persuadable than older adults (Krosnick & Alwin, 1989), possibly because younger people are still forming many of their attitudes and have less firmly established beliefs.

Modern research highlights that people are most persuaded when messages feel self-relevant and consistent with their existing identity—echoing recent developments in cognitive dissonance theory. Personalized or tailored messages, including those generated algorithmically, tend to be more effective than generic appeals.

- Bryan, C. J., Walton, G. M., Rogers, T., & Dweck, C. S. (2011). Motivating voter turnout by invoking the self. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(31), 12653–12656. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1103343108 ↵