Supernatural Perspectives of Psychological Disorders

For much of human history, psychological disorders were explained through supernatural causes—forces beyond scientific understanding. People who showed unusual thoughts, emotions, or behaviors were sometimes believed to be cursed, possessed by spirits, or practicing black magic (Maher & Maher, 1985).

For example, historical records from Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries describe convent episodes in which groups of nuns entered intense states of frenzy—screaming, convulsing, reporting visions, and making shocking confessions. Today, some of these behaviors might be interpreted through the lens of mental illness or mass psychological phenomena, but at the time they were commonly explained as demonic possession (Waller, 2009a). Similar interpretations appeared during the witch panic in late 17th-century New England, where unusual “fits” in young girls were widely viewed through a supernatural framework (Demos, 1983).

Beliefs in supernatural causes of mental illness have not disappeared entirely. In some societies today, spiritual or supernatural explanations for mental illness remain common and influence how people seek help (Aghukwa, 2012).

Dancing Mania

Between the 11th and 17th centuries, Western Europe experienced a strange phenomenon sometimes called dancing mania. Large groups of people would suddenly begin dancing uncontrollably—sometimes for days or even weeks (Figure 2). Historical accounts describe dancers continuing until their feet were bruised and bleeding, while some screamed, begged for religious intervention, or reported frightening visions (Waller, 2009b).

No single explanation has been proven, but several have been proposed over time, including physical causes such as poisoning (for example, ergot exposure) as well as psychological and social causes (“Dancing Mania,” 2011).

Historian John Waller (2009a, 2009b) offers a widely discussed explanation that connects psychological distress, social contagion, and cultural beliefs. He argued that repeated disasters of the era—famine, disease, floods, and instability—created intense stress. In that context, people who already believed in spiritual curses or possession may have been more likely to enter trance-like states. Once a few individuals began “dancing,” others could follow, especially when the behavior matched the expectations and beliefs of the culture. In other words, the symptoms were shaped not only by distress, but also by the stories people had available to explain that distress.

Biological Perspectives of Psychological Disorders

In contrast to supernatural explanations, the biological perspective links psychological disorders to biological factors such as genetics, brain structure and function, and neurochemistry. This approach has gained strong scientific support over time (Wyatt & Midkiff, 2006).

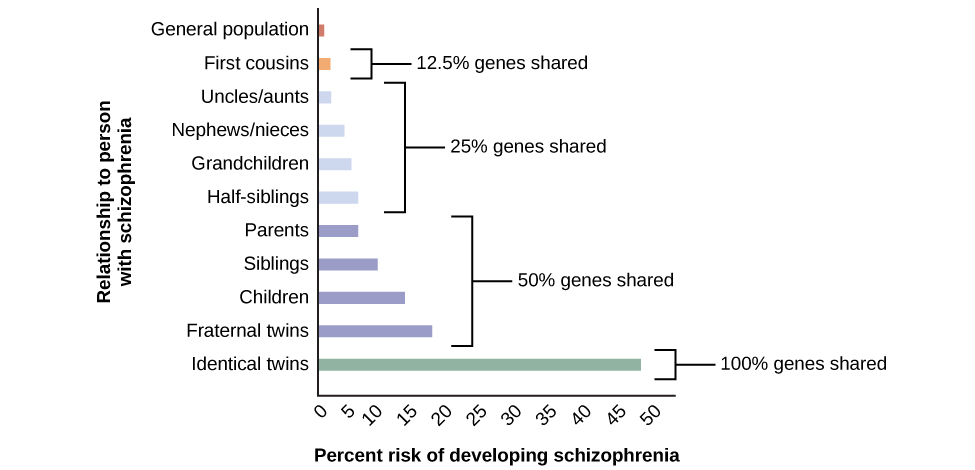

Evidence from many sources suggests that many disorders have a genetic component, though genes rarely tell the whole story. For example, schizophrenia shows heritability patterns such that risk increases when close relatives are affected (Figure 3).

Findings such as these have led many of today’s researchers to search for specific genes and genetic mutations that contribute to mental disorders. Also, sophisticated neural imaging technology in recent decades has revealed how abnormalities in brain structure and function might be directly involved in many disorders, and advances in our understanding of neurotransmitters and hormones have yielded insights into their possible connections. The biological perspective is currently thriving in the study of psychological disorders.

The Diathesis-Stress Model of Disorders

Even with advances in biology, psychological and environmental factors remain essential for understanding mental disorders. The psychosocial perspective emphasizes learning, stress, maladaptive thinking patterns, and social and environmental conditions.

A widely used way to integrate these viewpoints is the diathesis-stress model (Zuckerman, 1999).

the diathesis-stress model

The diathesis-stress model

proposes that many disorders develop through an interaction between:

-

diathesis: an underlying vulnerability (biological or psychological)

-

stress: environmental or psychological strain (e.g., trauma, chronic stress, major life disruptions)

A diathesis might be genetic risk, but it could also be psychological—for example, a tendency to interpret challenges in a pessimistic or self-defeating way.

A key idea in the model is that vulnerability and stress work together. In general:

-

higher vulnerability → less stress needed to trigger symptoms

-

lower vulnerability → more stress required to trigger symptoms

This model helps explain why two people can go through similar stressors and have very different mental health outcomes.