- Describe job analysis and the initial steps in employee selection

- Understand how employees are assessed and selected

- Describe types of job training and performance assessment

Job Analysis

The branch of I-O psychology known as industrial psychology focuses on identifying and matching persons to tasks within an organization.

This involves job analysis, which means accurately describing the task or job. Then, organizations must identify the characteristics of applicants for a match to the job analysis. It also involves training employees from their first day on the job throughout their tenure within the organization, and appraising their performance along the way.

The Job Description

When you read a job ad, you’re looking at the results of job analysis.

One major piece of job analysis is task-oriented: listing the tasks a person performs on the job. Tasks are often rated by:

- how often they occur

- how difficult they are

- how important they are to success

For example, a retail sales clerk might help customers find products, answer questions, use a register, make change, bag merchandise, and close out transactions. When those tasks are clearly described, organizations can:

- build a realistic job posting

- identify training needs

- decide what behaviors should be rewarded (and what performance problems should be addressed)

The Job Specification

The second major piece of job analysis is worker-oriented: describing the worker characteristics needed to perform the job well. This is called a job specification.

Traditionally, I-O psychologists describe job requirements using KSAs:

- Knowledge: what someone needs to know (e.g., store policies, product info)

- Skills: what someone can do (e.g., communication, conflict de-escalation)

- Abilities: more stable capabilities (e.g., math ability, attention to detail)

Returning to the retail example, the job specification might emphasize being friendly, reliable, detail-oriented, and able to learn product information quickly. This information matters because it shapes the selection system—how the company decides who is likely to succeed.

Using O*NET to Explore Job Requirements

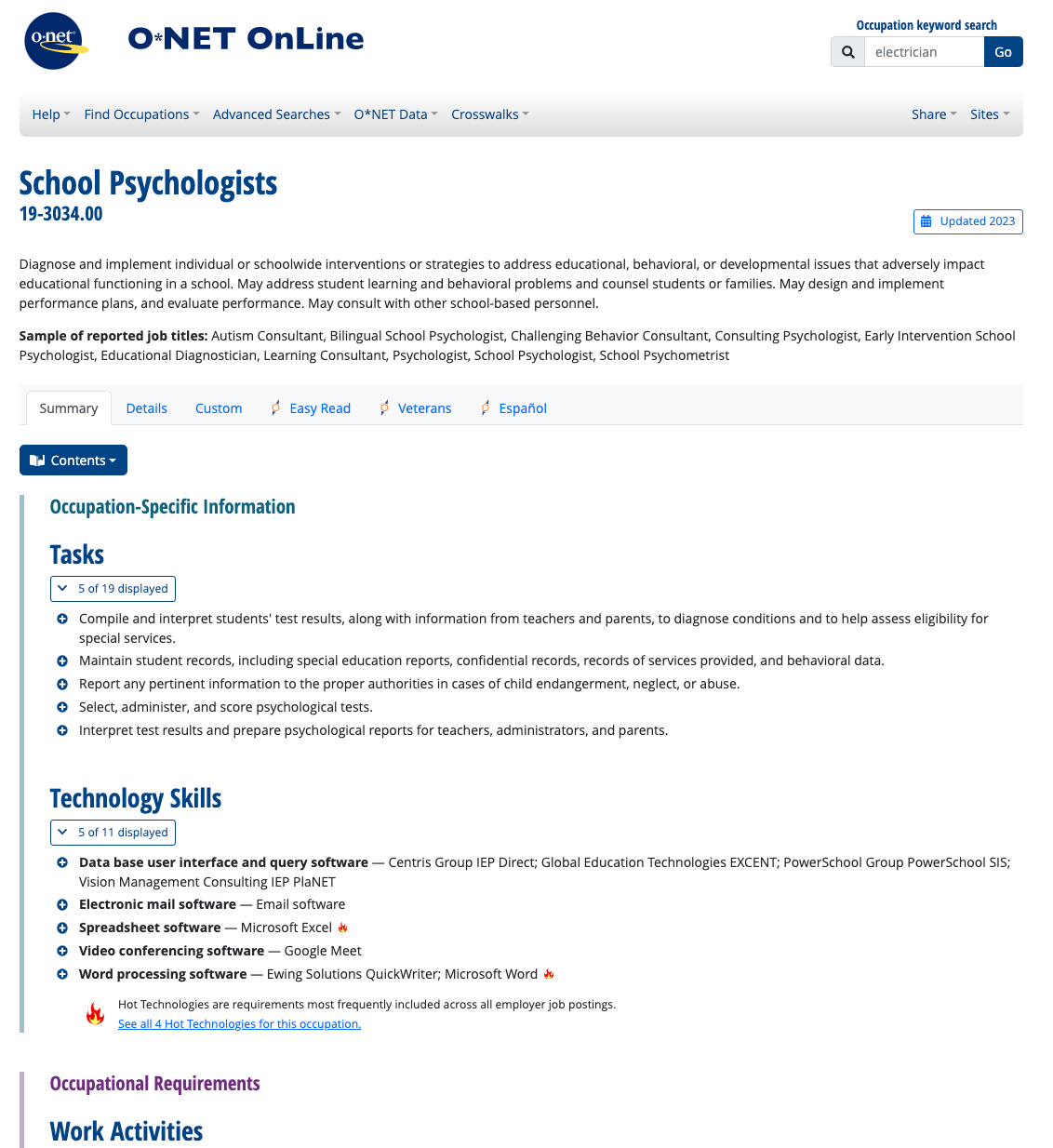

In the U.S., the Department of Labor supports a major job-analysis database called O*NET. It includes detailed profiles for 900+ occupations, such as:

- key tasks and work activities

- required knowledge, skills, and abilities

- work context and working conditions

- typical education and training

- interests and work styles associated with success

- wage and outlook information

Candidate Analysis and Testing

Once a company has a clear job description and job specification, the next step is evaluating applicants and identifying the strongest match.

Selection tools often include:

- structured interviews (same questions for every candidate)

- work samples or exercises (showing you can do key tasks)

- cognitive or job-knowledge tests

- personality measures

- integrity tests

- physical requirements tests (when job-relevant)

- drug testing (depending on role and local policy/law)

Personality tests, for example, are sometimes used to match a candidate’s traits to job demands. In a customer support role, higher agreeableness might seem helpful. But extremely high agreeableness could sometimes backfire—if it leads someone to agree with a customer’s misunderstanding rather than confidently correcting it and solving the problem.

That’s why selection tools should be validated—meaning the organization needs evidence that scores actually relate to job performance in that specific context (and that the tool doesn’t unfairly screen out groups in ways that aren’t job-related).

Today, many employers use software-based screening tools (including algorithmic scoring of résumés, assessments, or video interviews). I-O psychologists are increasingly involved in evaluating whether these tools are job-related and valid, fair across groups, and used appropriately (as one data point, not a “magic” decider).

To better understand the hiring process, let’s consider an example case. A company determined it had an open position and advertised it. The human resources (HR) manager directed the hiring team to start the recruitment process. People saw the advertisement and submitted their résumés, which went into the collection of candidate résumés. The HR team reviewed the candidates’ credentials and provided a list of the best potential candidates to the department manager, who reached out to them to set up individual interviews.

What Do You Think? Using Cutoff Scores to Determine Job Selection

Many positions require applicants to take tests as part of the selection process. These can include IQ tests, job-specific skills tests, or personality tests. The organization may set cutoff scores (i.e., a score below which a candidate will not move forward) for each test to determine whether the applicant moves on to the next stage.

For example, there was a case of Robert Jordan, a 49-year-old college graduate who applied for a position with the police force in New London, Connecticut. As part of the selection process, Jordan took the Wonderlic Personnel Test (WPT), a test designed to measure cognitive ability.

Jordan did not make it to the interview stage because his WPT score of 33, equivalent to an IQ score of 125 (100 is the average IQ score), was too high. The New London Police department policy was to not interview anyone who has a WPT score over 27 (equivalent to an IQ score over 104) because they believe anyone who scores higher would be bored with police work. The average score for police officers nationwide is the equivalent of an IQ score of 104 (Jordan v. New London, 2000; ABC News, 2000).

Jordan sued the police department alleging that his rejection was discrimination and that his civil rights were violated because he was denied equal protection under the law. The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a lower court’s decision that the city of New London did not discriminate against him because the same standards were applied to everyone who took the exam (The New York Times, 1999).

Although the court upheld the policy, many I-O psychologists view this case as an example of how a selection practice can be legally defensible yet scientifically questionable. Today, most organizations rely on multiple validated selection tools rather than rigid upper cutoff scores.

What do you think? When might universal cutoff points make sense in a hiring decision, and when might they eliminate otherwise potentially strong employees?