- Describe examples of Gestalt principles

- Understand multimodal perception

- Give examples of multimodal and crossmodal behavioral effects

- Explain how and why psychologists use illusions

- Discuss real-life examples of the Ebbinghaus illusion

Gestalt Principles and Perception

In the early part of the 20th century, Max Wertheimer published a paper demonstrating that individuals perceived motion in rapidly flickering static images—an insight that came to him as he used a tachistoscope (an older type of those viewfinders that display one image at a time and then rotate through other images). Wertheimer, and his assistants Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka, who later became his partners, believed that perception involved more than simply combining sensory stimuli. This belief led to a new movement within the field of psychology known as Gestalt psychology.

Gestalt psychology

The word gestalt literally means form or pattern, but its use reflects the idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. In other words, the brain creates a perception that is more than simply the sum of available sensory inputs, and it does so in predictable ways.

Gestalt psychologists translated these predictable ways into principles by which we organize sensory information. As a result, Gestalt psychology has been extremely influential in the area of sensation and perception (Rock & Palmer, 1990).

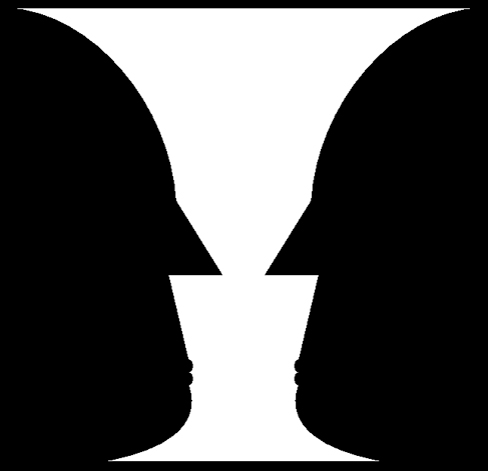

One Gestalt principle is the figure-ground relationship.

figure-ground relationship

According to this principle, we tend to segment our visual world into figure and ground. Figure is the object or person that is the focus of the visual field, while the ground is the background.

As Figure 1 shows, our perception can vary tremendously, depending on what is perceived as figure and what is perceived as ground. Presumably, our ability to interpret sensory information depends on what we label as the figure and what we label as the ground in any particular case, although this assumption has been called into question (Peterson & Gibson, 1994; Vecera & O’Reilly, 1998).

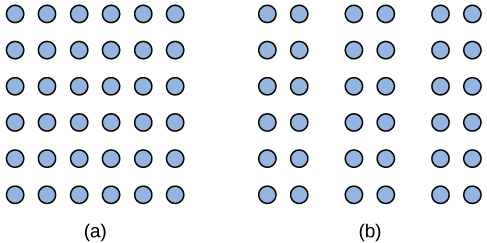

Another Gestalt principle for organizing sensory stimuli into meaningful perception is proximity.

proximity

This principle asserts that things that are close to one another tend to be grouped together, as Figure 2 illustrates.

How we read something provides another illustration of the proximity concept. For example, we read this sentence like this, notl iket hiso rt hat. We group the letters of a given word together because there are no spaces between the letters, and we perceive words because there are spaces between each word. Here are some more examples: Cany oum akes enseo ft hiss entence? What doth es e wor dsmea n?

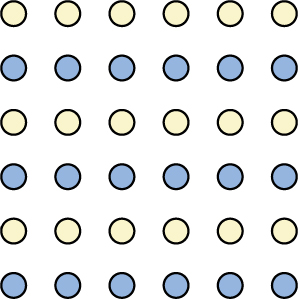

We might also use the principle of similarity to group things in our visual fields.

similarity

According to this principle, things that are alike tend to be grouped together (Figure 3). For example, when watching a football game, we tend to group individuals based on the colors of their uniforms. When watching an offensive drive, we can get a sense of the two teams simply by grouping along this dimension.

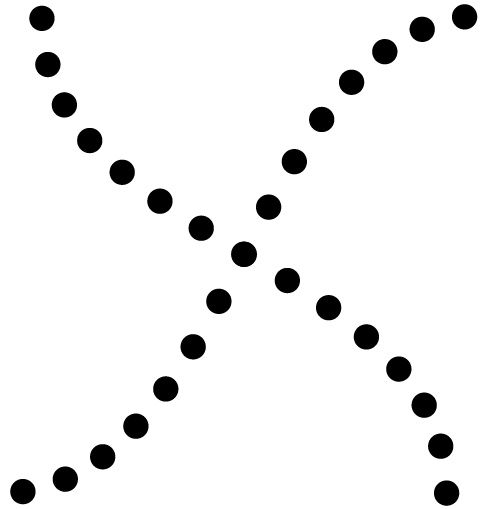

Two additional Gestalt principles are the law of continuity (or good continuation) and closure.

law of continuity

The law of continuity suggests that we are more likely to perceive continuous, smooth flowing lines rather than jagged, broken lines (Figure 4).

closure

The principle of closure states that we organize our perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts (Figure 5).

According to Gestalt theorists, pattern perception, or our ability to discriminate among different figures and shapes, occurs by following the principles described above. You probably feel fairly certain that your perception accurately matches the real world, but this is not always the case.

Our perceptions are based on perceptual hypotheses: educated guesses that we make while interpreting sensory information. These hypotheses are informed by a number of factors, including our personalities, experiences, and expectations. We use these hypotheses to generate our perceptual set. For instance, research has demonstrated that those who are given verbal priming produce a biased interpretation of complex ambiguous figures (Goolkasian & Woodbury, 2010).

The Depths of Perception: Bias, Prejudice, and Cultural Factors

Perception is shaped not just by sensory input but by our experiences, expectations, and social environments. Unfortunately, these factors can contribute to implicit bias.

Research shows:

- Non-Black participants identify weapons more quickly when paired with images of Black faces and are more likely to falsely identify neutral objects as weapons (Payne, 2001; Payne et al., 2005).

- In a simulated “shoot/don’t shoot” task, White participants were quicker to “shoot” armed Black targets and more likely to mistakenly “shoot” unarmed Black targets (Correll et al., 2002; Correll et al., 2006).

These findings have real-world implications for understanding how perceptual biases contribute to unequal treatment and tragic outcomes in policing and everyday life.