Antisocial Personality Disorder

Most people learn early that other people have rights and feelings, and that choices like lying, cheating, stealing, or hurting others have consequences. Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) involves a long-term pattern of behavior in which those social rules are repeatedly ignored or violated. The key issue isn’t “being a bad person”—it’s a persistent pattern of disregard for others’ rights and safety, often alongside impulsivity and poor responsibility.

antisocial personality disorder

In the DSM-5-TR, ASPD is defined by a pervasive pattern (across many situations) of violating others’ rights, beginning in adolescence and continuing into adulthood. Common features include:

-

Repeated rule-breaking or illegal behavior

-

Deceitfulness, such as lying, using aliases, or conning others for personal gain

-

Impulsivity or poor planning

-

Irritability and aggressiveness, including frequent fights or assaults

-

Reckless disregard for safety of self or others

-

Chronic irresponsibility, such as repeatedly failing to work consistently or honor financial obligations

-

Lack of remorse, such as being indifferent to—or rationalizing—having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from someone

A diagnosis requires the person to be at least 18 years old, and there must be evidence of conduct problems before age 15 (often described as conduct disorder symptoms). This matters because clinicians look for a long-standing pattern—not a single incident or a short “rough period.”

- Disinhibition is a propensity toward impulse control problems, lack of planning and forethought, insistence on immediate gratification, and inability to restrain behavior.

- Boldness describes a tendency to remain calm in threatening situations, high self-assurance, a sense of dominance, and a tendency toward thrill-seeking.

- Meanness is defined as “aggressive resource seeking without regard for others,” and is signaled by a lack of empathy, disdain for and lack of close relationships with others, and a tendency to accomplish goals through cruelty (Patrick et al., 2009, p. 913).

Not every person with ASPD shows all three traits strongly. That’s one reason people with the same diagnosis can look very different from one another.

Risk Factors for Antisocial Personality Disorder

Antisocial personality disorder is observed in about 3.6% of the population; the disorder is much more common among males, with a 3 to 1 ratio of men to women, and it is more likely to occur in men who are younger, widowed, separated, divorced, of lower socioeconomic status, who live in urban areas, and who live in the western United States (Compton, Conway, Stinson, Colliver, & Grant, 2005). Compared to men with antisocial personality disorder, women with the disorder are more likely to have experienced emotional neglect and sexual abuse during childhood, and they are more likely to have had parents who abused substances and who engaged in antisocial behaviors themselves (Alegria et al., 2013).

The table below shows some of the differences in the specific types of antisocial behaviors that men and women with antisocial personality disorder exhibit (Alegria et al., 2013).

| Men with antisocial personality disorder are more likely than women with antisocial personality disorder to: | Women with antisocial personality disorder are more likely than men with antisocial personality to: |

|---|---|

|

|

Family, twin, and adoption studies suggest that both genetic and environmental factors influence the development of antisocial personality disorder, as well as general antisocial behavior (criminality, violence, aggressiveness) (Baker, Bezdjian, & Raine, 2006). Personality and temperament dimensions that are related to this disorder, including fearlessness, impulsive antisociality, and callousness, have a substantial genetic influence (Livesley & Jang, 2008). Adoption studies clearly demonstrate that the development of antisocial behavior is determined by the interaction of genetic factors and adverse environmental circumstances (Rhee & Waldman, 2002).

For example, one investigation found that adoptees of biological parents with antisocial personality disorder were more likely to exhibit adolescent and adult antisocial behaviors if they were raised in adverse adoptive family environments (e.g., adoptive parents had marital problems, were divorced, used drugs, and had legal problems) than if they were raised in a more normal adoptive environment (Cadoret, Yates, Ed, Woodworth, & Stewart, 1995).

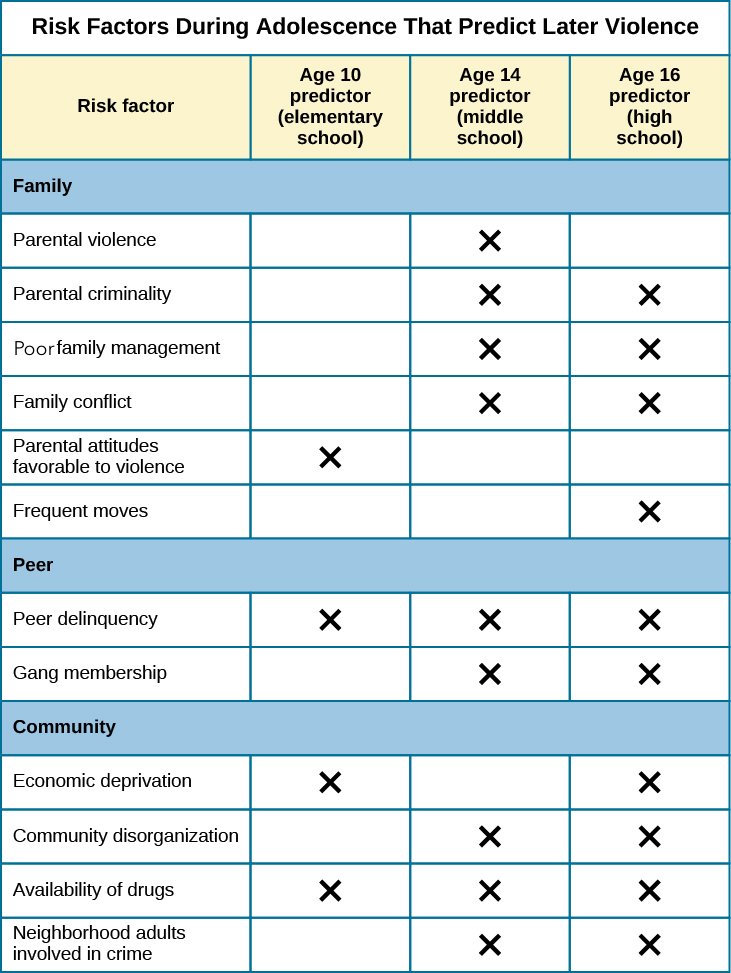

Researchers who are interested in the importance of the environment in the development of antisocial personality disorder have directed their attention to such factors as the community, the structure and functioning of the family, and peer groups. Each of these factors influences the likelihood of antisocial behavior. One longitudinal investigation of more than 800 Seattle-area youth measured risk factors for violence at 10, 14, 16, and 18 years of age (Herrenkohl et al., 2000). The risk factors examined included those involving the family, peers, and community. A portion of the findings from this study are provided in Figure 1.

Those with antisocial tendencies do not seem to experience emotions the way most other people do. These individuals fail to show fear in response to environmental cues that signal punishment, pain, or noxious stimulation. For instance, they show less skin conductance (sweatiness on hands) in anticipation of electric shock than do people without antisocial tendencies (Hare, 1965). Skin conductance is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system and is used to assess autonomic nervous system functioning. When the sympathetic nervous system is active, people become aroused and anxious, and sweat gland activity increases. Thus, increased sweat gland activity, as assessed through skin conductance, is taken as a sign of arousal or anxiety. For those with antisocial personality disorder, a lack of skin conductance may indicate the presence of characteristics such as emotional deficits and impulsivity that underlie the propensity for antisocial behavior and negative social relationships (Fung et al., 2005).

While emotional deficits may contribute to antisocial personality disorder, so too might an inability to relate to others’ pain. In one study, 80 prisoners were shown photos of people being intentionally hurt by others (e.g., someone crushing a person’s hand in an automobile door) while undergoing brain imaging (Decety, Skelly, & Kiehl, 2013). Prisoners who scored high on a test of antisocial tendencies showed significantly less activation in brain regions involved in the experience of empathy and feeling concerned for others than did prisoners with low scores on the antisocial test. Notably, the prisoners who scored high on the antisocial test showed greater activation in a brain area involved self-awareness, cognitive function, and interpersonal experience. The investigators suggested that the heightened activation in this region when watching social interactions involving one person harming another may reflect a propensity or desire for this kind of behavior.