What Do We Talk About?

What are humans doing when we are talking? Surely, we can communicate about mundane things such as what to have for dinner, but also more complex and abstract things such as the meaning of life and death, liberty, equality, and many other philosophical thoughts.

When observed, 60-70% of everyday conversation is gossip, which some argue is one of the most critical uses of language (Dunbar, Marriott, & Duncan, 1997).

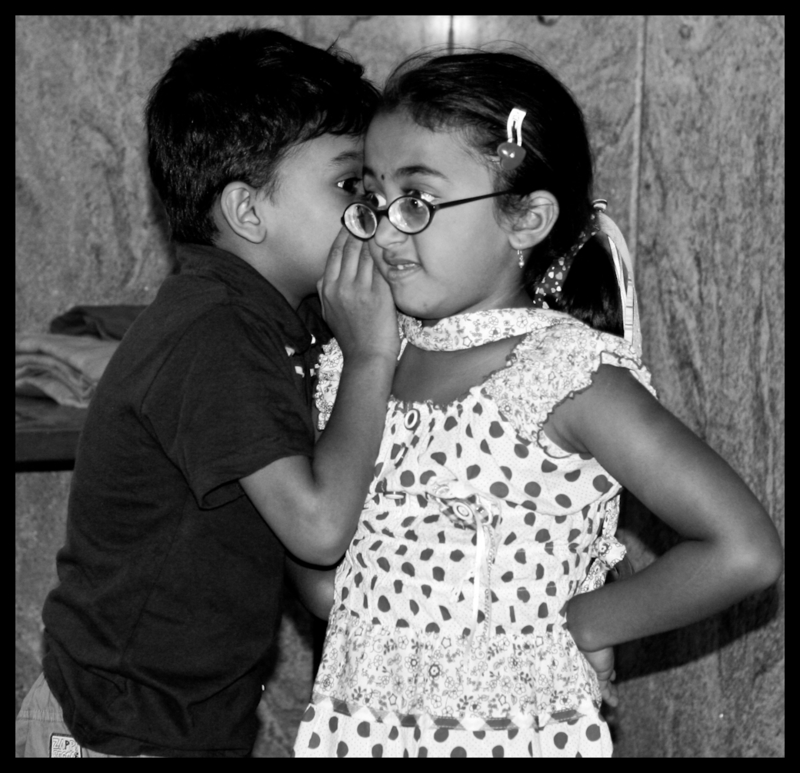

gossip

Gossip is when people talk about themselves and others whom they know.

Gossiping is compared to grooming in primates and is an act of socializing and signaling the importance of one’s partner. Through gossip, humans can share their representations of the social world (who their friends and enemies are, what the right thing to do is under what circumstances, etc.) and regulate their social world by maintaining larger ingroups.

ingroups and outgroups

Ingroups refer to groups of people with whom one identifies and shares a common identity, such as family, friends, or colleagues. Outgroups, on the other hand, are groups of people who are seen as different from one’s ingroup and may be perceived as outsiders, rivals, or enemies.

This social use of language has been studied as an evolutionary advantage.

social brain hypothesis

Dunbar has argued that it is these social effects that have given humans an evolutionary advantage and larger brains, which, in turn, help humans to think more complex and abstract thoughts and, more important, maintain larger ingroups.

According to his social brain hypothesis, Dunbar showed that those primates that have larger brains tend to live in larger groups.

Dunbar (1993) estimated an equation that predicts average group size of nonhuman primates based on the average neocortex size (the part of the brain that supports higher order cognition). Furthermore, using the same equation, he was able to estimate the group size that human brains can support, which turned out to be about 150—approximately the size of modern hunter-gatherer communities. Dunbar’s argument is that language, brain, and human group living have co-evolved—language and human sociality are inseparable. Dunbar’s hypothesis is controversial and more recent research reveals that there is no set number or limit of possible group connections.[1] Nonetheless, whether or not he is right, our everyday language use often ends up maintaining the existing structure of intergroup relationships.

Language use can have implications for how we construe our social world. For one thing, there are subtle cues that people use to convey the extent to which someone’s action is just a special case in a particular context or a pattern that occurs across many contexts and more like a character trait of the person. According to Semin and Fiedler (1988), someone’s action can be described by an action verb that describes a concrete action (e.g., he runs), a state verb that describes the actor’s psychological state (e.g., he likes running), an adjective that describes the actor’s personality (e.g., he is athletic), or a noun that describes the actor’s role (e.g., he is an athlete). Depending on whether a verb or an adjective (or noun) is used, speakers can convey the permanency and stability of an actor’s tendency to act in a certain way—verbs convey particularity, whereas adjectives convey permanency.

Intriguingly, people tend to describe positive actions of their ingroup members using adjectives (e.g., he is generous) rather than verbs (e.g., he gave that person some change), and negative actions of outgroup members using adjectives (e.g., he is cruel) rather than verbs (e.g., he kicked a dog). Maass, Salvi, Arcuri, and Semin (1989) called this a linguistic intergroup bias, which can produce and reproduce the representation of intergroup relationships by painting a picture favoring the ingroup. That is, ingroup members are typically good, and if they do anything bad, that’s more an exception in special circumstances; in contrast, outgroup members are typically bad, and if they do anything good, that’s more an exception.

In addition, when people exchange their gossip, it can spread through broader social networks from one person to another. This often happens for stories that evoke strong emotions.

If gossip is repeatedly transmitted and spread, it can reach a large number of people. When stories travel through communication chains, they tend to become conventionalized (Bartlett, 1932). In other words, information transmitted multiple times was transformed to something that was easily understood by many, that is, information was assimilated into the common ground shared by most people in the linguistic community.

More recently, Kashima (2000) conducted a similar experiment using a story that contained sequence of events that described a young couple’s interaction that included both stereotypical and counter-stereotypical actions (e.g., a man watching sports on TV on Sunday vs. a man vacuuming the house). After the retelling of this story, much of the counter-stereotypical information was dropped, and stereotypical information was more likely to be retained. Because stereotypes are part of the common ground shared by the community, this finding too suggests that conversational retellings are likely to reproduce conventional content.

- Lindenfors Patrik, Wartel Andreas and Lind Johan 2021‘Dunbar's number’ deconstructed. Biol. Lett.172021015820210158 http://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2021.0158 ↵