Motivations, Expectations, and Perception

Motivation can also affect perception. Have you ever been expecting a really important phone call and, while taking a shower, you think you hear the phone ringing, only to discover that it is not? If so, then you have experienced how motivation to detect a meaningful stimulus can shift our ability to discriminate between a true sensory stimulus and background noise.

signal detection theory

Signal detection theory is the ability to identify a stimulus when it is embedded in a distracting background. This might also explain why a mother is awakened by a quiet murmur from her baby but not by other sounds that occur while she is asleep.

Signal detection theory has practical applications, such as increasing air traffic controller accuracy. Controllers need to be able to detect planes among many signals (blips) that appear on the radar screen and follow those planes as they move through the sky. In fact, the original work of the researcher who developed signal detection theory was focused on improving the sensitivity of air traffic controllers to plane blips (Swets, 1964).

More recent research has applied signal detection theory far beyond its original use in radar and aviation. For example, in cardiac interoception studies, researchers use the theory to measure how accurately people can detect their own heartbeats without checking their pulse (Lamb et al., 2020). This work helps scientists understand how bodily awareness relates to anxiety, stress, and emotional regulation.

Another example comes from traffic safety research, where signal detection theory helps identify the minimum safe passing distance between drivers and cyclists (Pohl et al., 2021). By studying how drivers perceive a cyclist’s position and speed under different visual and environmental conditions, researchers can recommend safer road designs and distance guidelines.

Our beliefs, expectations, and experiences also shape perception. For example, individuals deprived of binocular vision early in life later struggle to perceive depth (Fawcett, Wang, & Birch, 2005). Likewise, shared experiences within a culture can influence what we see—or think we see.

Classic Findings on Culture and Perception

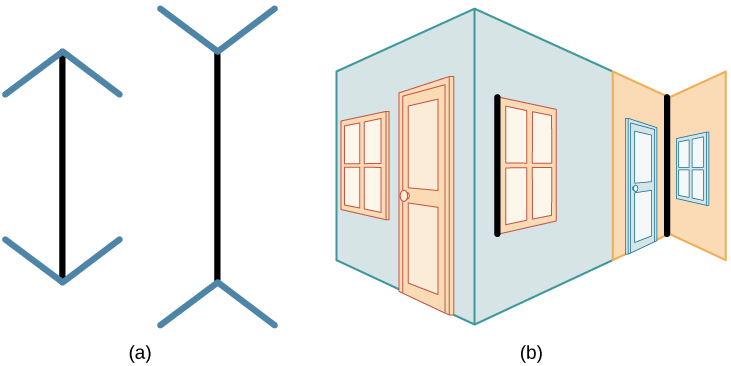

A famous multinational study by Segall, Campbell, and Herskovits (1963) showed that people from Western cultures were more likely to be fooled by the Müller-Lyer illusion—where two identical lines appear different in length (shown below).

Researchers proposed that this difference reflected environmental experience: Westerners grow up surrounded by rectangular buildings and right angles, creating what they called a “carpentered world.” By contrast, people in non-Western settings, such as the Zulu of South Africa, who traditionally live in circular huts, were less susceptible to the illusion (Segall et al., 1999).

A Modern View: Culture and Biology Working Together

Recent research challenges the idea that illusions like the Müller-Lyer are purely cultural. In Is Visual Perception WEIRD? Amir and Firestone (2024) reexamined the “carpentered world” hypothesis and found that the illusion appears across species (birds, monkeys, and fish can fall for the illusion), sensory modalities (it can work with touch as well), and cultures, even in individuals without prior visual experience. They argue that this illusion reflects universal features of human (and even animal) perception, not just Western visual learning. So, rather than being a Western cultural artifact, this illusion probably reveals something universal about how perception works across species and senses.[1]

In short, culture still shapes how we interpret sensory information, but many perceptual processes—like those behind visual illusions—appear to be rooted in shared biological mechanisms that all humans rely on.

Cultural and Individual Differences Beyond Vision

Perception also varies in other senses:

- People from different cultures differ in how they identify and rate odors, including how pleasant or intense they seem (Ayabe-Kanamura et al., 1998).

- Thrill-seeking children often prefer more intense sour flavors (Liem et al., 2004).

- People who hold positive attitudes toward reduced-fat foods often rate them as tasting better, showing how expectations influence perception (Aaron et al., 1994).

- Amir, D., & Firestone, C. (2025). Is visual perception WEIRD? The Müller-Lyer illusion and the cultural byproduct hypothesis. Psychological Review, 132(1), 45–67. https://perception.jhu.edu/files/PDFs/25_MullerLyer/AmirFirestone_MullerLyer_2025_PsychReview.pdf ↵