Causality: Conducting Experiments and Using the Data

As you’ve learned, the only way to establish that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between two variables is to conduct a scientific experiment. In order to conduct an experiment, a researcher must have a specific hypothesis to be tested. Hypotheses can be formulated either through direct observation of the real world or after careful review of previous research and theories. to find out if real-world data supports our hypothesis, we have to conduct an experiment.

Designing an Experiment

experimental and control groups

The most basic experimental design involves two groups: the experimental group and the control group. The two groups are designed to be the same except for one difference— experimental manipulation.

The experimental group gets the experimental manipulation—that is, the treatment or variable being tested—and the control group does not. Since experimental manipulation is the only difference between the experimental and control groups, we can be sure that any differences between the two are due to experimental manipulation rather than chance.

Experiment: What works best for learning algebra?

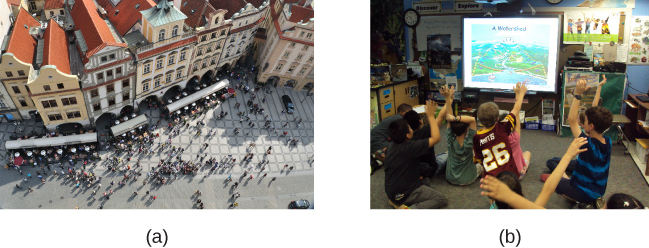

Say we want to study the impact of a new program on learning. We could have the experimental group learn algebra using the new computer program and then test their learning. We measure the learning against our control group after they are taught algebra by a teacher in a traditional classroom. It is important for the control group to be treated similarly to the experimental group, with the exception that the control group does not receive the experimental manipulation.

Operationalize

We also need to precisely define, or operationalize, how we measure the variables in our study.

operational definition

An operational definition is a precise description of our variables, and it is important in allowing others to understand exactly how and what a researcher measures in a particular experiment.

In operationalizing this study on learning, we would explain what we mean by “learning” and how that will be measured—perhaps by a test, or by having the students summarize the information they learned. Whatever we determine, it is important that we operationalize learning in such a way that anyone who hears about our study for the first time knows exactly what we mean by learning. This aids peoples’ ability to interpret our data as well as their capacity to replicate, or repeat, our experiment should they choose to do so.

Choose Participants

Participants are the subjects of psychological research, and as the name implies, individuals who are involved in psychological research actively participate in the process.

Samples are used because populations are usually too large to reasonably involve every member in our particular experiment. If possible, we should use a random sample.

random sample

A random sample is a subset of a larger population in which every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. Random samples are preferred because if the sample is large enough we can be reasonably sure that the participating individuals are representative of the larger population. This means that the percentages of characteristics in the sample—sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic level, and any other characteristics that might affect the results—are close to those percentages in the larger population.

In our example, let’s say we decide our population of interest is fourth graders. But all fourth graders is a very large population, so we need to be more specific; instead, we might say our population of interest is all fourth graders in a particular city. We should include students from various income brackets, family situations, races, ethnicities, religions, and geographic areas of town. With this more manageable population, we can work with the local schools in selecting a random sample of around 200 fourth graders who we want to participate in our experiment. With a representative group, we can generalize our findings to the larger population.

Representative and Random Samples

A representative sample accurately reflects the demographics and diversity of the larger population (in this case, all U.S. adults). To achieve this, researchers often use random sampling, where every individual has an equal chance of being selected.

In its simplest form, random sampling means assigning each person a number and using a computer to randomly choose participants. While most modern surveys don’t use this exact process, they rely on probability-based methods to ensure fairness and avoid bias.

For example, the GSS selects participants from nationally representative panels using established sampling techniques.

The General Social Survey (GSS)

One of the most widely used examples is the General Social Survey (GSS), conducted every two years in the United States.

Each cycle, researchers survey about 2,000-3,000 adult Americans to measure attitudes and behaviors on topics like:

- Political ideology (e.g., how many identify as liberal or conservative)

- Well-being (e.g., what percentage describe themselves as happy)

- Lifestyle and time use (e.g., how many people feel rushed each day)

Despite surveying only a few thousand people, researchers can draw conclusions about the entire U.S. adult population—as long as the sample is representative.

In the 2024 survey, participants were asked:

“Taken all together, how would you say things are these days—would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?”

Here’s what the results showed:

Out of about 3,300 respondents:

- 684 said they were very happy; or 23.3% (± 1.13)

- 1,892 said pretty happy, or 56.0% (± 1.05)

- 705 said not too happy; or 20.3% (± 1.05)

- A few skipped or didn’t know (about 1%)

Because the GSS uses probability-based sampling, researchers can be confident that these percentages closely reflect national trends.

Why Results Vary from Sample to Sample

Even with a large, representative sample, no survey gives exactly the same result each time. If another random sample of Americans were surveyed, the percentages might be slightly different—perhaps 22% or 24% “very happy” instead of exactly 23%.

This natural variation happens because we’re studying a subset of the population, not everyone. Statisticians use tools like standard deviation and margin of error to describe this uncertainty.

Standard Deviation: Measuring Spread

Standard deviation measures how much individual responses differ from the average (mean) response.

- A small standard deviation = most responses cluster near the average

- A large standard deviation = responses are widely spread out

Example with quiz scores: Imagine five students take a 100-point psychology quiz:

Scenario 1: Scores are 70, 72, 74, 76, 78

- Mean = 74

- Scores are tightly clustered (within 4 points)

- Standard deviation ≈ 3 points (small)

Scenario 2: Scores are 50, 60, 70, 80, 90

- Mean = 70

- Scores are widely spread (40-point range)

- Standard deviation ≈ 15 points (large)

In psychology research, standard deviation reveals whether a behavior or attitude is consistent across people or highly variable.

Applying This to Surveys

In surveys like the GSS, researchers measure proportions or percentages rather than individual scores. The standard error (a type of standard deviation for samples) captures expected variation between samples.

If the GSS were repeated multiple times with different random groups, the percentage saying “very happy” would fluctuate slightly—maybe 22%, 24%, 23%. The standard error quantifies this “bounce.”

In the GSS happiness example, the standard error of 1.13 percentage points reflects the typical variation expected across repeated samples of the same size.

Margin of Error: Creating Confidence Intervals

The margin of error converts standard deviation into an interpretable range, answering: “How close is our sample result likely to be to the true population value?”

Researchers typically use a 95% confidence level, meaning that if we repeated the survey 100 times, approximately 95 of those surveys would produce results within the margin of error.

If 23.3% of respondents say they’re “very happy,” with a margin of error of ±1.13%, we can conclude: We are 95% confident that between 22.17% and 24.43% of all American adults are “very happy.”

This range is called a confidence interval—a way of acknowledging that our data come from a sample, not the entire population.