- Understand how loss of function in different brain areas can help us study the brain

- Describe the ways that brains can be imaged or scanned

Studying the Human Brain

How do we know what the brain does? We have gathered knowledge about the functions of the brain from many different methods. Each method is useful for answering distinct types of questions, but the strongest evidence for a specific role or function of a particular brain area is converging evidence; that is, similar findings reported from multiple studies using different methods.

One of the first organized attempts to study the functions of the brain was phrenology, a popular field of study in the first half of the 19th century. Phrenologists assumed that various features of the brain, such as its uneven surface, are reflected on the skull; therefore, they attempted to correlate bumps and indentations of the skull with specific functions of the brain. For example, they would claim that a very artistic person has ridges on the head that vary in size and location from those of someone who is very good at spatial reasoning. Although the assumption that the skull reflects the underlying brain structure has been proven wrong, phrenology nonetheless significantly impacted current-day neuroscience and its thinking about the functions of the brain. That is, different parts of the brain are devoted to specific functions that can be identified through scientific inquiry.

Studying the Brain: Injuries or Lesions

Another way to learn about brain function is to study changes in the behavior and ability of individuals who have suffered damage to the brain. For example, researchers study the behavioral changes caused by strokes to learn about the functions of specific brain areas.

A stroke, caused by an interruption of blood flow to a region in the brain, causes a loss of brain function in the affected region. The damage can be in a small area, and, if it is, this gives researchers the opportunity to link any resulting behavioral changes to a specific area. The types of deficits displayed after a stroke will be largely dependent on where in the brain the damage occurred.

For example, this stroke survivor has damage to his posterior temporal lobe, causing Wernicke’s Aphasia, which is marked by his fluent, yet non-sensical speech.

You can view the transcript for “Fluent Aphasia (Wernicke’s Aphasia)” here (opens in new window).

Consider Theona, an intelligent, self-sufficient woman, who is 62 years old. Recently, she suffered a stroke in the front portion of her right hemisphere. As a result, she has great difficulty moving her left leg. (As you learned earlier, the right hemisphere controls the left side of the body; also, the brain’s main motor centers are located at the front of the head, in the frontal lobe.) Theona has also experienced behavioral changes. For example, while in the produce section of the grocery store, she sometimes eats grapes, strawberries, and apples directly from their bins before paying for them. This behavior—which would have been very embarrassing to her before the stroke—is consistent with damage in another region in the frontal lobe—the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with judgment, reasoning, and impulse control.

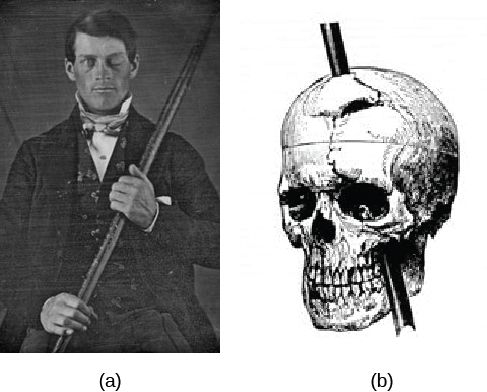

The Story of Phineas Gage

Probably the most famous case of frontal lobe damage is that of a man by the name of Phineas Gage. On September 13, 1848, Gage (age 25) was working as a railroad foreman in Vermont. He and his crew were using an iron rod to tamp explosives down into a blasting hole to remove rock along the railway’s path. Unfortunately, the iron rod created a spark and caused the rod to explode out of the blasting hole, into Gage’s face, and through his skull.

Although lying in a pool of his blood with brain matter emerging from his head, Gage was conscious and able to get up, walk, and speak. But in the months following his accident, people noticed that his personality had changed. Many of his friends described him as no longer being himself. Before the accident, it was said that Gage was a well-mannered, soft-spoken man, but he began to behave in odd and inappropriate ways after the accident. Such changes in personality would be consistent with loss of impulse control—a frontal lobe function.

Beyond the damage to the frontal lobe itself, subsequent investigations into the rod’s path also identified probable damage to pathways between the frontal lobe and other brain structures, including the limbic system. With connections between the planning functions of the frontal lobe and the emotional processes of the limbic system severed, Gage had difficulty controlling his emotional impulses.

However, there is some evidence suggesting that the dramatic changes in Gage’s personality were exaggerated and embellished. Gage’s case occurred amid a 19th century debate over localization—regarding whether certain areas of the brain are associated with particular functions. On the basis of extremely limited information about Gage, the extent of his injury, and his life before and after the accident, scientists tended to find support for their own views, on whichever side of the debate they fell (Macmillan, 1999).

You can watch a summary about Gage’s accident and injury in this creative lego stop-motion video (or view the transcript here).

Some researchers induce lesions or ablate (i.e., remove) parts of the brain in animals. If the animal’s behavior changes after the lesion, we can infer that the removed structure is important for that behavior.

Lesions of the human brain are studied in patient populations only; that is, patients who have lost a brain region due to a stroke or other injury, or who have had surgical removal of a structure to treat a particular disease. From such case studies, we can infer brain function by measuring changes in the behavior of the patients before and after the lesion.