Causes of Schizophrenia

There is considerable evidence suggesting that schizophrenia has a genetic basis. The risk of developing schizophrenia is nearly 6 times greater if one has a parent with schizophrenia than if one does not (Goldstein, Buka, Seidman, & Tsuang, 2010). Additionally, one’s risk of developing schizophrenia increases as genetic relatedness to family members diagnosed with schizophrenia increases (Gottesman, 2001).

Genetic Contributions

Evidence from Family and Adoption Studies

When studying the genetics of any disorder, conclusions from family and twin studies face an important limitation: closely related family members typically share similar environments, making it difficult to separate genetic from environmental influences. Adoption studies help address this problem by examining children raised apart from their biological parents.

One landmark adoption study by Heston (1966) followed 97 adoptees over 36 years, including 47 born to mothers with schizophrenia. Five of these 47 adoptees (11%) later developed schizophrenia, compared to none of the 50 control adoptees. Subsequent adoption studies consistently show that biological relatives of people with schizophrenia have higher schizophrenia rates than adoptive relatives (Shih, Belmonte, & Zandi, 2004).

The Diathesis-Stress Model

Adoption studies demonstrate that schizophrenia arises from the interaction of genetic vulnerability and environmental factors—not genes alone. A pivotal study by Tienari and colleagues (2004) examined 303 adoptees: 145 with biological mothers who had schizophrenia (high genetic risk) and 158 whose mothers had no psychiatric history (low genetic risk). Researchers also assessed whether adoptees were raised in healthy versus disturbed family environments.

The findings were striking:

- High genetic risk + disturbed family environment: 36.8% developed schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder

- High genetic risk + healthy environment: 5.8% developed the disorder

- Low genetic risk + disturbed environment: 5.3% developed the disorder

- Low genetic risk + healthy environment: 4.8% developed the disorder

These results support the diathesis-stress model: genetic vulnerability alone isn’t sufficient—environmental stress must also be present for schizophrenia to develop in most cases.

Modern Genetic Research

Today’s large-scale genome studies have identified hundreds of genetic variants associated with schizophrenia risk. The largest genome-wide association study (GWAS) to date—including over 76,000 patients—identified 287 genetic variants linked to the disorder. Many of these implicate genes involved in synaptic organization, neurotransmitter signaling, and immune function (Trubetskoy et al., 2022).

One of the most significant genetic findings involves complement component 4 (C4), part of the immune system. Research published in Nature demonstrated that genetic variants increasing C4A expression in the brain are associated with higher schizophrenia risk. The C4 protein localizes to synapses and plays a role in synaptic pruning—the normal process of eliminating unnecessary neural connections during development. In schizophrenia, excessive C4 activity may lead to over-pruning of synapses, potentially explaining the reduced neural connectivity observed in the disorder (Sekar et al., 2016; Yilmaz et al., 2021).

This finding provides a potential mechanism linking genetic risk to the structural brain changes observed in schizophrenia—and may explain why the disorder typically emerges during adolescence and early adulthood, when synaptic pruning naturally peaks.

Many schizophrenia risk genes also increase risk for bipolar disorder, autism, and other neurodevelopmental conditions, suggesting shared biological pathways across these disorders (Tandon et al., 2024).

Neurotransmitter Systems

The Dopamine Hypothesis

Interest in dopamine’s role in schizophrenia emerged from two key observations: drugs that increase dopamine can produce schizophrenia-like symptoms, and medications that block dopamine reduce symptoms (Howes & Kapur, 2009).

The original dopamine hypothesis proposed that excess dopamine or too many dopamine receptors cause schizophrenia (Snyder, 1976). Modern research has refined this view, recognizing that dopamine abnormalities vary by brain region and contribute to different symptoms:

- Mesolimbic pathway (from ventral tegmental area to limbic system): Excess dopamine activity may drive positive symptoms—hallucinations and delusions

- Mesocortical pathway (from ventral tegmental area to prefrontal cortex): Reduced dopamine activity may contribute to negative symptoms and cognitive deficits

This “two-pathway” model helps explain why dopamine-blocking medications effectively treat positive symptoms but often have limited impact on negative and cognitive symptoms (Davis et al., 1991; McCutcheon et al., 2020).

Beyond Dopamine: The Glutamate Hypothesis

While dopamine dysfunction remains central to understanding schizophrenia, it cannot fully explain the disorder—particularly negative symptoms and cognitive impairment. This led researchers to investigate glutamate, the brain’s primary excitatory neurotransmitter.

The glutamate hypothesis arose from observations that drugs blocking NMDA glutamate receptors (such as ketamine and PCP) produce symptoms remarkably similar to schizophrenia—including positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms (Javitt & Zukin, 1991).

Current understanding suggests both systems interact:

- Reduced NMDA receptor function on inhibitory neurons may lead to excess glutamate release

- This glutamate excess may then trigger downstream dopamine dysregulation

- Patients who don’t respond to traditional dopamine-blocking medications may have predominantly glutamate-based dysfunction (Howes et al., 2015)

The 2024 FDA approval of Cobenfy (xanomeline-trospium)—which works through acetylcholine receptors rather than dopamine—represents the first new medication mechanism in over 70 years and opens new treatment avenues beyond the dopamine system.

Research also implicates that other neurotransmitters impact schizophrenia, including:

- Serotonin: Many newer antipsychotic medications block serotonin receptors in addition to dopamine receptors (Baumeister & Hawkins, 2004)

- GABA: The brain’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter may be reduced in schizophrenia, contributing to the excitation-inhibition imbalance

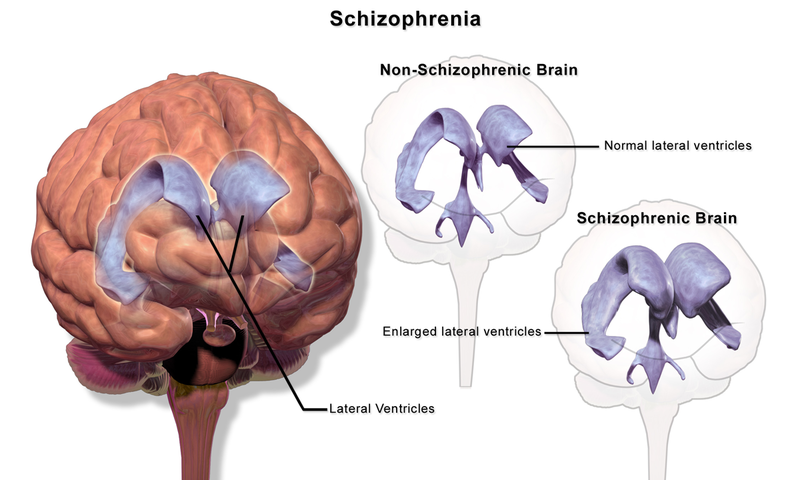

Figure 1. Schizophrenia is associated with enlarged ventricles in the brain.

Brain Anatomy and Structure

Neuroimaging studies consistently reveal structural brain differences in people with schizophrenia. Key findings include:

- Reduced gray matter volume in the prefrontal cortex, temporal lobes, and hippocampus

- Enlarged ventricles (fluid-filled spaces in the brain) Larger than normal ventricles suggests that various brain regions are reduced in size, thus implying that schizophrenia is associated with a loss of brain tissue.

- Cortical thinning particularly in frontal and temporal regions

- Progressive gray matter loss especially in early-onset cases during the first years after illness onset

A 2024 meta-analysis identified consistent structural abnormalities in the inferior frontal gyri and superior temporal gyrus—regions involved in language processing, social cognition, and auditory processing (Wang et al., 2024).

Obstetric Complications and Prental Infections

Why do people with schizophrenia have brain abnormalities? Several environmental factors that impact normal brain development may be involved.

High rates of birth complications have been reported in children who later developed schizophrenia (Cannon, Jones, & Murray, 2002). Complications during delivery that reduce oxygen supply to the brain (perinatal hypoxia) may disrupt normal neurodevelopment.

People face increased risk for developing schizophrenia if their mother was exposed to influenza during the first trimester of pregnancy (Brown et al., 2004). Research suggests that the maternal immune response to infection—rather than the virus itself—may affect fetal brain development. A 2024 study found that some schizophrenia-related genetic mutations show molecular signatures consistent with inflammation, supporting this connection between prenatal infection and later risk (Mount Sinai, 2024).

A mother’s emotional stress during pregnancy may also increase offspring’s schizophrenia risk. One study found that risk was elevated substantially in offspring whose mothers experienced the death of a relative during the first trimester of pregnancy (Khashan et al., 2008).

Brain Connectivity

Beyond regional volume changes, schizophrenia involves altered communication between brain regions. Recent research using functional MRI (fMRI) has identified:

- Disrupted connectivity between prefrontal cortex and other brain regions

- Altered patterns in brain networks involved in attention, memory, and social processing

- Age-related connectivity changes during late adolescence and early adulthood that may relate to when symptoms typically emerge

A 2023 neuroimaging study found that alterations in prefrontal-sensorimotor and cerebellar-occipitoparietal brain connections are linked to genetic risk for schizophrenia—even in unaffected siblings of patients (Passiatore et al., 2023).

The “Epicenter” Model

Research suggests schizophrenia may originate in specific brain regions (“epicenters”) and spread to connected areas over time—similar to patterns observed in neurodegenerative diseases. The anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and temporal regions have been identified as potential epicenters, though individual patients may show different patterns (Science Advances, 2024).

Cannabis (Marijuana) Use

Cannabis use is a well-established risk factor for schizophrenia, particularly when use begins during adolescence.

While people with schizophrenia are more likely to use cannabis than those without the disorder, longitudinal studies confirm that cannabis use often precedes and contributes to schizophrenia development—not just the reverse.

A landmark study of over 45,000 Swedish military conscripts found that those who had used cannabis at least once by age 18 were more than twice as likely to develop schizophrenia over the next 15 years. Those who had used cannabis 50 or more times were six times as likely to develop the disorder (Andréasson et al., 1987). A review of 35 longitudinal studies confirmed substantially increased risk, with the greatest risk among the most frequent users (Moore et al., 2007).

A major 2023 study analyzing health records of over 6.9 million people in Denmark found that cannabis use disorder is strongly associated with schizophrenia in both sexes—but the association is much stronger in young men. Researchers estimated that:

- 30% of schizophrenia cases among men aged 21-30 might have been prevented by averting cannabis use disorder

- 15% of cases among all men aged 16-49 might have been prevented

- The proportion of schizophrenia cases attributable to cannabis use disorder has increased over the past five decades—likely due to rising cannabis potency

Today’s cannabis products are far more potent than in the past: THC concentrations now regularly exceed 17-28%, with some concentrates reaching above 90%. This increased potency may partly explain the growing association between cannabis use and schizophrenia (Hjorthøj et al., 2023).

Why Adolescence Matters

Cannabis is not an essential or sufficient cause of schizophrenia—not everyone with schizophrenia has used cannabis, and most cannabis users never develop the disorder (Casadio et al., 2011). However, adolescent use appears particularly risky because:

- The brain continues developing into the mid-20s

- Cannabis may disrupt normal neurodevelopmental processes during this critical period

- Early use may “set the stage” for schizophrenia in genetically vulnerable individuals

The endocannabinoid system—which cannabis targets—plays important roles in brain development, and disruptions during adolescence may increase vulnerability to psychotic symptoms (Trezza et al., 2008).

Early Warning Signs:

Neuroimaging Biomarkers

Researchers are actively working to develop neuroimaging-based biomarkers that could help diagnose schizophrenia or predict who among at-risk individuals will develop the disorder:

- Neuromelanin-sensitive MRI shows promise as a marker of dopamine function and symptom severity

- Machine learning algorithms applied to brain scans can distinguish patients with schizophrenia from healthy controls with increasing accuracy

- Functional connectivity patterns may help identify distinct subtypes of schizophrenia with different treatment needs

The Accelerating Medicines Partnership Schizophrenia (AMP SCZ)—a major international research initiative—is working to identify biological markers that predict transition to psychosis in at-risk individuals.

While neuroimaging is not yet used routinely for diagnosis, these advances hold promise for:

- Earlier identification of at-risk individuals

- Personalized treatment selection based on individual brain patterns

- Better prediction of treatment response

- Tracking disease progression and treatment effects

Prodromal Symptoms

Researchers have identified prodromal symptoms—subtle warning signs that may appear months or years before a full psychotic episode:

- Unusual thought content

- Paranoia or suspiciousness

- Odd communication patterns

- Mild delusions

- Problems at school or work

- Decline in social functioning

Predicting Who Will Develop Psychosis

Not everyone with prodromal symptoms develops schizophrenia—in fact, only about 10-20% of individuals identified as “clinical high risk” transition to a full psychotic disorder within two years. Research has identified factors that predict greater likelihood of progression (Fusar-Poli et al., 2013):

- Genetic risk: Family history of psychosis

- Recent deterioration: Declining functioning over time

- High levels of unusual thought content

- Suspicion or paranoia

- Poor social functioning

- History of substance abuse