- Explain the difference between M1 and M2 money supply

- Explain the role of banks

- Understand the functions of the Federal Reserve System

- Understand what the Federal Reserve System does to carry out monetary policy

The U.S. Banking System

Now that you have a good understanding of money, what qualifies as money, and how money facilitates exchanges between buyers and sellers, we need to look at how money evolves from a medium of exchange to a system.

What Is Included in the Money Supply?

Cash in your wallet certainly serves as money, but how about checks or credit cards? Are they money, too? Rather than trying to determine a single way of measuring money, economists use broader definitions of money based on liquidity. Liquidity refers to how quickly a financial asset can be used to buy a good or service. For example, cash is very liquid. Your $10 bill can easily be used to buy a hamburger at lunchtime. However, $10 that you have in your savings account is not so easy to use. You must first go to the bank or ATM machine and withdraw that cash to buy your lunch. Thus, $10 in your savings account is less liquid than cash in your pocket.

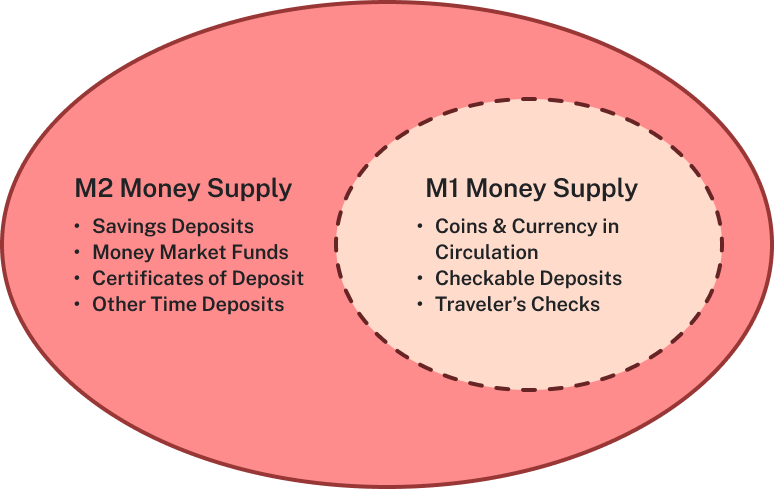

The Federal Reserve Bank, which is the central bank of the United States, is a bank regulator. It’s responsible for monetary policy, and it defines money according to its liquidity. There are two categories of money: M1 and M2 money supply.

M1 and M2 money supply

M1 money supply includes those monies that are very liquid such as cash and demand deposits.

M2 money supply is less liquid in nature and includes M1 monies, plus savings and time deposits and other money that is not immediately available.

M1 money supply includes coins and currency that circulate in an economy and are not held by the U.S. Treasury, at the Federal Reserve Bank, or in bank vaults. Closely related to currency are checkable deposits, also known as demand deposits. These are the amounts held in checking accounts. They are called demand deposits or checkable deposits, because the banking institution must give the deposit holder their money “on demand” when a check is written or a debit card is used. Circulating currency and demand deposits in banks make up the money defined as M1 and it is measured daily by the Federal Reserve System.

M2 is a broader category of money. It includes everything in M1 but also adds other types of deposits. For example, M2 includes savings deposits in banks, which are bank accounts on which you cannot write a check directly, but from which you can easily withdraw the money at an automatic teller machine or bank. Many banks and other financial institutions also offer a chance to invest in money market funds, where the deposits of many individual investors are pooled together and invested in a safe way, such as in short-term government bonds. Another portion of M2 is certificates of deposit (CDs) and other time deposits, which are accounts that the depositor has committed to leaving in the bank for a certain period of time, ranging from a few months to a few years, in exchange for a higher interest rate. All these types of M2 are money that you can withdraw and spend, but which require a greater effort to do so than the items in M1.

Measuring the Money Supply

The Federal Reserve System is responsible for tracking the amounts of M1 and M2 and prepares a weekly release of information about the money supply. For example, according to the Federal Reserve Bank’s measure of the U.S. money stock, in March 2025, M1 in the United States was $18.56 trillion, while M2 was $21.62 trillion. The Federal Reserve Bank reports a breakdown of the portion of each type of money that comprised M1 and M2 each month.[1]

The lines separating M1 and M2 can become a little blurry. Sometimes elements of M1 are not treated alike; for example, some businesses will not accept personal checks for large amounts but will accept cash. Changes in banking practices and technology have made the savings accounts in M2 more similar to the checking accounts in M1. For example, some savings accounts will allow depositors to write checks, use automatic teller machines, and pay bills over the Internet, which has made it easier to access savings accounts.

Plastic Money

Where does “plastic money” like debit cards, credit cards, and smart money fit into this picture? A debit card, like a check, is an instruction to the user’s bank to transfer money directly and immediately from your bank account to the seller. It is important to note that it is the money in the demand deposits that is counted as money, not the paper check or the debit card. Although you can make a purchase with a credit card, it is not considered money but rather a short-term loan from the credit card company to you. When you make a purchase with a credit card, the credit card company immediately transfers money from its checking account to the seller, and at the end of the month, the credit card company sends you a bill for what you have charged that month. Until you pay the credit card bill, you have basically borrowed money from the credit card company.

In short, credit cards and debit cards are different ways to move money when a purchase is made. But having more credit cards or debit cards does not change the quantity of money in the economy, any more than having more checks printed increases the amount of money in your checking account. One key message here is that counting and tracking the money in a modern economy doesn’t just involve paper bills and coins; instead, money is closely linked to bank accounts. Indeed, the macroeconomic policies concerning money are largely conducted through the banking system. The next section explains how banks function as an intermediary to financial transactions.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Money Stock Measures. https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h6/current/default.htm ↵