- Spot indeterminate forms like in calculations, and use L’Hôpital’s rule to find precise values

- Explain how quickly different functions increase or decrease compared to each other

L’Hôpital’s Rule

L’Hôpital’s Rule is a powerful technique for evaluating limits of functions. It leverages derivatives to determine limits that are otherwise challenging to compute directly, providing a clear way to resolve indeterminate forms.

Applying L’Hôpital’s Rule

L’Hôpital’s Rule comes into play when you’re dealing with limits that result in indeterminate forms.

Consider the quotient of two functions, represented as:

If [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=L_1[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)=L_2 \ne 0[/latex], then

However, what happens if [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=0[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)=0[/latex]?

We call this one of the indeterminate forms, of type [latex]\frac{0}{0}[/latex]. This is considered an indeterminate form because we cannot determine the exact behavior of [latex]\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}[/latex] as [latex]x\to a[/latex] without further analysis. We have seen examples of this earlier in the text.

- [latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}\dfrac{x^2-4}{x-2}[/latex] can be solved by factoring the numerator and simplifying.

[latex]\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}\dfrac{x^2-4}{x-2}=\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}\dfrac{(x+2)(x-2)}{x-2}=\underset{x\to 2}{\lim}(x+2)=2+2=4[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\lim}\frac{\sin x}{x}[/latex] has been proven geometrically to equal [latex]1[/latex]. Using L’Hôpital’s Rule, differentiating both numerator and denominator yields:

[latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\lim}\dfrac{\sin x}{x}=1[/latex]

L’Hôpital’s Rule not only simplifies the calculation of certain limits but also provides insights into evaluating complex limits that would be difficult to handle by other methods. This rule is particularly useful in analyzing the behavior of functions as they approach critical points.

L’Hôpital’s Rule (0/0 Case)

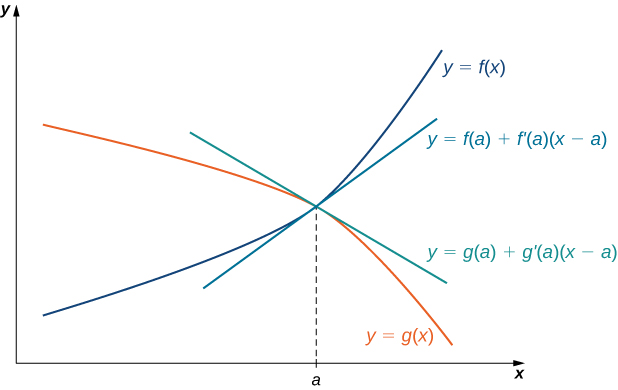

The idea behind L’Hôpital’s rule can be explained using local linear approximations.

Consider two differentiable functions [latex]f[/latex] and [latex]g[/latex] such that [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=0=\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)[/latex] and such that [latex]g^{\prime}(a)\ne 0[/latex] For [latex]x[/latex] near [latex]a[/latex], we can write

and

Therefore,

Since [latex]f[/latex] is differentiable at [latex]a[/latex], then [latex]f[/latex] is continuous at [latex]a[/latex], and therefore [latex]f(a)=\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=0[/latex]. Similarly, [latex]g(a)=\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)=0[/latex]. If we also assume that [latex]f^{\prime}[/latex] and [latex]g^{\prime}[/latex] are continuous at [latex]x=a[/latex], then [latex]f^{\prime}(a)=\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f^{\prime}(x)[/latex] and [latex]g^{\prime}(a)=\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g^{\prime}(x)[/latex].

Using these ideas, we conclude that:

Note that the assumption that [latex]f^{\prime}[/latex] and [latex]g^{\prime}[/latex] are continuous at [latex]a[/latex] and [latex]g^{\prime}(a)\ne 0[/latex] can be loosened.

The notation [latex]\frac{0}{0}[/latex] does not mean we are actually dividing zero by zero. Rather, we are using the notation [latex]\frac{0}{0}[/latex] to represent a quotient of limits, each of which is zero.

We state L’Hôpital’s rule formally for the indeterminate form [latex]\frac{0}{0}[/latex].

L’Hôpital’s rule (0/0 case)

Suppose [latex]f[/latex] and [latex]g[/latex] are differentiable functions over an open interval containing [latex]a[/latex], except possibly at [latex]a[/latex]. If [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=0[/latex] and [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)=0[/latex], then

assuming the limit on the right exists or is [latex]\infty[/latex] or [latex]−\infty[/latex]. This result also holds if we are considering one-sided limits, or if [latex]a=\infty[/latex] or [latex]-\infty[/latex].

Proof

We provide a proof of this theorem in the special case when [latex]f, \, g, \, f^{\prime}[/latex], and [latex]g^{\prime}[/latex] are all continuous over an open interval containing [latex]a[/latex]. In that case, since [latex]\underset{x\to a}{\lim}f(x)=0=\underset{x\to a}{\lim}g(x)[/latex] and [latex]f[/latex] and [latex]g[/latex] are continuous at [latex]a[/latex], it follows that [latex]f(a)=0=g(a)[/latex]. Therefore,

Note that L’Hôpital’s rule states we can calculate the limit of a quotient [latex]\frac{f}{g}[/latex] by considering the limit of the quotient of the derivatives [latex]\frac{f^{\prime}}{g^{\prime}}[/latex]. It is important to realize that we are not calculating the derivative of the quotient [latex]\frac{f}{g}[/latex].

[latex]_\blacksquare[/latex]

Evaluate each of the following limits by applying L’Hôpital’s rule.

- [latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\lim}\dfrac{1- \cos x}{x}[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to 1}{\lim}\dfrac{\sin (\pi x)}{\ln x}[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to \infty }{\lim}\dfrac{e^{\frac{1}{x}}-1}{\frac{1}{x}}[/latex]

- [latex]\underset{x\to 0}{\lim}\dfrac{\sin x-x}{x^2}[/latex]